'All eyes are on Kathmandu's Balen Shah': Not 2025, the fall of Nepal's old guard began in 2022

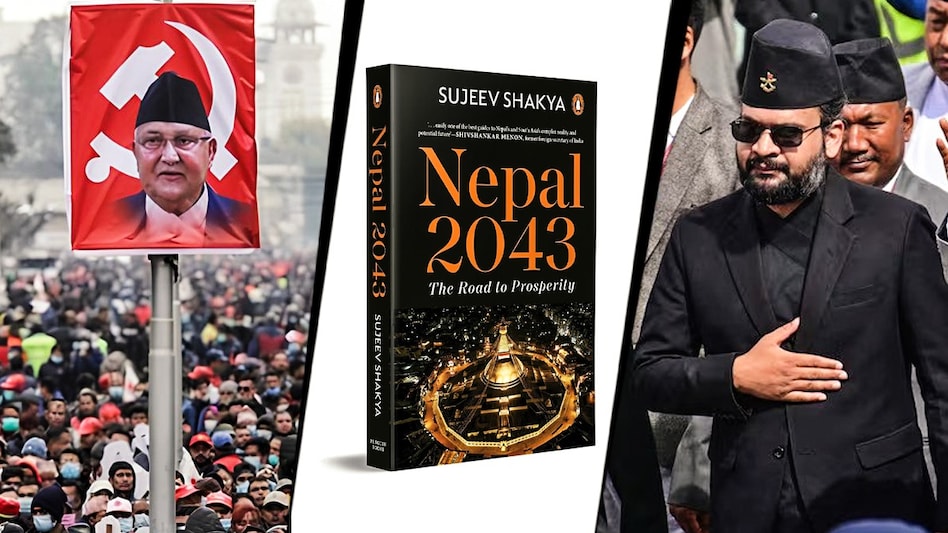

'In a country where 70 per cent of the population is below the age of forty, old male leaders have been given a wake-up call and a clear message that they should hang up their hats,' writes Sujeev Shakya in his new book, Nepal 2043

- Dec 10, 2025,

- Updated Dec 10, 2025 12:58 PM IST

Nepal's youth may have revolted in 2025, but the political ground against the established parties and their leaders had already started shifting in 2022.

Sujeev Shakya, dubbed by many as a chief eternal optimist, has come out with a new book that details the changes in the political space over the last few years, anger against corruption, and the emergence of new leaders who the author predicts may end the domination of old parties.

In 'Nepal 2043: The Road to Prosperity', published in September, Shakya tracks Nepal's political and economic journey and how this Himalayan country that is, contrary to the belief, is not-so-small and can leverage its strategic position. He points out that Nepal, which is land-linked with India and China, can tag along with two neighbouring Asian giants to become a high-income country by 2043.

The first sign of change in the political wind came in 2022, when local elections were held in May and the federal election in November. In the local elections, 81 per cent of the candidates elected were new faces. "It was a strong anti-incumbent vote," writes Shakya.

In Dharan in eastern Nepal, Harka Rai Sampang, a lone campaigner who did not belong to any political party, became the mayor. Sampang, according to the author, campaigned with a small budget, and support proved that money is not the only ingredient necessary to win elections.

In that same year, a group of independent candidates formed a new party, the Rashtriya Swatantra Party (RSP) and became the fourth-largest force in Nepal's Parliament.

"There was a strong #NoNotAgain campaign against the old, male politicians across established parties who have been dominant for the past three decades," highlights Shakya, founder and chair of the Nepal Economic Forum. Many of the old politicians lost the re-election as 50% of those elected were parliamentarians for the first time. "I wrote then that 'New faces in Nepal's politics, a phase of change' has begun."

Shakya, who leads Beed Management - a Nepal-based management consulting and financial advisory firm - also refers to a visible change that people with no money muscle were now getting elected. He states that popular wisdom has always dictated that to win elections, one had to spend money and pay for a ticket from a major political party. This time, however, there were thousands who joined the fray with few resources or connections. "And they actually won with a decent number of votes. This has changed the game."

The next setback for the old guard came when an RSP member wrested a parliamentary seat, held by Ram Chandra Paudel, the current President of Nepal.

The Tanahu-1 parliamentary constituency fell vacant when Ram Chandra Paudel, a Nepali Congress member, was elected Nepal's President. In the 2023 by-poll, Swarnim Wagle, a Harvard-educated development professional and noted economist, wrested the seat by defeating candidates from two established parties. "His journey from leaving NC to joining RSP, contesting the elections, and winning was undertaken in twenty-five days! There is a change happening, and it is happening at a rapid pace," writes Shakya.

There are five key forces in Nepal: the Nepali Congress, the Communist faction, the turncoats who have joined every cabinet, royalists who use the revival of the monarchy and the Hindu kingdom as their agenda, and the emerging breed of new politicians. The Nepali Congress is largely a dynast-driven party, while the Communist parties are led by the old guard, who are very hesitant to open the doors for young politicians. This emerging group of politicians, Shakya writes, includes those who have formed the RSP and independent candidates, such as Kathmandu mayor Balendra Shah.

The RSP was formed in June 2022 by Rabi Lamichhane, just six months before the federal elections. He returned from the US in 2017, renounced his US citizenship, joined a television channel as an anchor and hosted a popular show that was projected as a voice for the voiceless. Many independent candidates came together under the RSP banner with Rabi as Chairman.

The RSP managed to win thirteen seats directly and, by securing 12.19 per cent of the vote, gained seven seats through proportional representation. "This party became a symbol of hope for Nepalis who sought an alternative to the quarrelling, inefficient, ageing male leaders of the traditional parties," notes Sakya. "For their part, the older parties see a threat from these new parties and are trying newer ways to impede their progress."

For example, RSP President Rabi Lamichhane, the author adds, was remanded to eighty-four days' custody in connection with an alleged cooperative scam. He was again arrested in April 2025 and continues to be in jail. He was briefly out of jail during the Gen Z protest in September, but returned to prison again.

The author outlines some key lessons from the 2022 elections that he believes will have a bearing on Nepal's journey towards 2043. Firstly, he says, "the way the people voted has disrupted the status quo. They voted for independents, looking at the candidates' competencies rather than their allegiances. Many senior party leaders had to swallow the bitter pill of their party’s candidate losing in the wards where they voted."

Shakya states that the 2022 elections were a wake-up call to those ruling the country for decades. "In a country where 70 per cent of the population is below the age of forty, old male leaders have been given a wake-up call and a clear message that they should hang up their hats. It is going to be important to watch how the traditional parties respond to this."

The author, in the book, does not cover the Gen Z protest in September, which the youth claimed was against nepotism and deepening corruption. The protest, which lasted just less than a week, forced Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and his cabinet ministers to step down. Once they stepped down, Nepal's President Poudel dissolved the House, and Sushila Karki, a former jurist, took over as interim PM. Now, Karki has announced fresh elections in March 2026, over a year before the scheduled polls in 2027.

"Finally, all eyes are on Kathmandu," Shakya concludes. "Much attention is focused on how a candidate like Balen Shah will perform. His success in Kathmandu could set a precedent for cities across Nepal. He has given hope to many young Nepalis that one can fight and an election and win it."

Nepal's youth may have revolted in 2025, but the political ground against the established parties and their leaders had already started shifting in 2022.

Sujeev Shakya, dubbed by many as a chief eternal optimist, has come out with a new book that details the changes in the political space over the last few years, anger against corruption, and the emergence of new leaders who the author predicts may end the domination of old parties.

In 'Nepal 2043: The Road to Prosperity', published in September, Shakya tracks Nepal's political and economic journey and how this Himalayan country that is, contrary to the belief, is not-so-small and can leverage its strategic position. He points out that Nepal, which is land-linked with India and China, can tag along with two neighbouring Asian giants to become a high-income country by 2043.

The first sign of change in the political wind came in 2022, when local elections were held in May and the federal election in November. In the local elections, 81 per cent of the candidates elected were new faces. "It was a strong anti-incumbent vote," writes Shakya.

In Dharan in eastern Nepal, Harka Rai Sampang, a lone campaigner who did not belong to any political party, became the mayor. Sampang, according to the author, campaigned with a small budget, and support proved that money is not the only ingredient necessary to win elections.

In that same year, a group of independent candidates formed a new party, the Rashtriya Swatantra Party (RSP) and became the fourth-largest force in Nepal's Parliament.

"There was a strong #NoNotAgain campaign against the old, male politicians across established parties who have been dominant for the past three decades," highlights Shakya, founder and chair of the Nepal Economic Forum. Many of the old politicians lost the re-election as 50% of those elected were parliamentarians for the first time. "I wrote then that 'New faces in Nepal's politics, a phase of change' has begun."

Shakya, who leads Beed Management - a Nepal-based management consulting and financial advisory firm - also refers to a visible change that people with no money muscle were now getting elected. He states that popular wisdom has always dictated that to win elections, one had to spend money and pay for a ticket from a major political party. This time, however, there were thousands who joined the fray with few resources or connections. "And they actually won with a decent number of votes. This has changed the game."

The next setback for the old guard came when an RSP member wrested a parliamentary seat, held by Ram Chandra Paudel, the current President of Nepal.

The Tanahu-1 parliamentary constituency fell vacant when Ram Chandra Paudel, a Nepali Congress member, was elected Nepal's President. In the 2023 by-poll, Swarnim Wagle, a Harvard-educated development professional and noted economist, wrested the seat by defeating candidates from two established parties. "His journey from leaving NC to joining RSP, contesting the elections, and winning was undertaken in twenty-five days! There is a change happening, and it is happening at a rapid pace," writes Shakya.

There are five key forces in Nepal: the Nepali Congress, the Communist faction, the turncoats who have joined every cabinet, royalists who use the revival of the monarchy and the Hindu kingdom as their agenda, and the emerging breed of new politicians. The Nepali Congress is largely a dynast-driven party, while the Communist parties are led by the old guard, who are very hesitant to open the doors for young politicians. This emerging group of politicians, Shakya writes, includes those who have formed the RSP and independent candidates, such as Kathmandu mayor Balendra Shah.

The RSP was formed in June 2022 by Rabi Lamichhane, just six months before the federal elections. He returned from the US in 2017, renounced his US citizenship, joined a television channel as an anchor and hosted a popular show that was projected as a voice for the voiceless. Many independent candidates came together under the RSP banner with Rabi as Chairman.

The RSP managed to win thirteen seats directly and, by securing 12.19 per cent of the vote, gained seven seats through proportional representation. "This party became a symbol of hope for Nepalis who sought an alternative to the quarrelling, inefficient, ageing male leaders of the traditional parties," notes Sakya. "For their part, the older parties see a threat from these new parties and are trying newer ways to impede their progress."

For example, RSP President Rabi Lamichhane, the author adds, was remanded to eighty-four days' custody in connection with an alleged cooperative scam. He was again arrested in April 2025 and continues to be in jail. He was briefly out of jail during the Gen Z protest in September, but returned to prison again.

The author outlines some key lessons from the 2022 elections that he believes will have a bearing on Nepal's journey towards 2043. Firstly, he says, "the way the people voted has disrupted the status quo. They voted for independents, looking at the candidates' competencies rather than their allegiances. Many senior party leaders had to swallow the bitter pill of their party’s candidate losing in the wards where they voted."

Shakya states that the 2022 elections were a wake-up call to those ruling the country for decades. "In a country where 70 per cent of the population is below the age of forty, old male leaders have been given a wake-up call and a clear message that they should hang up their hats. It is going to be important to watch how the traditional parties respond to this."

The author, in the book, does not cover the Gen Z protest in September, which the youth claimed was against nepotism and deepening corruption. The protest, which lasted just less than a week, forced Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and his cabinet ministers to step down. Once they stepped down, Nepal's President Poudel dissolved the House, and Sushila Karki, a former jurist, took over as interim PM. Now, Karki has announced fresh elections in March 2026, over a year before the scheduled polls in 2027.

"Finally, all eyes are on Kathmandu," Shakya concludes. "Much attention is focused on how a candidate like Balen Shah will perform. His success in Kathmandu could set a precedent for cities across Nepal. He has given hope to many young Nepalis that one can fight and an election and win it."