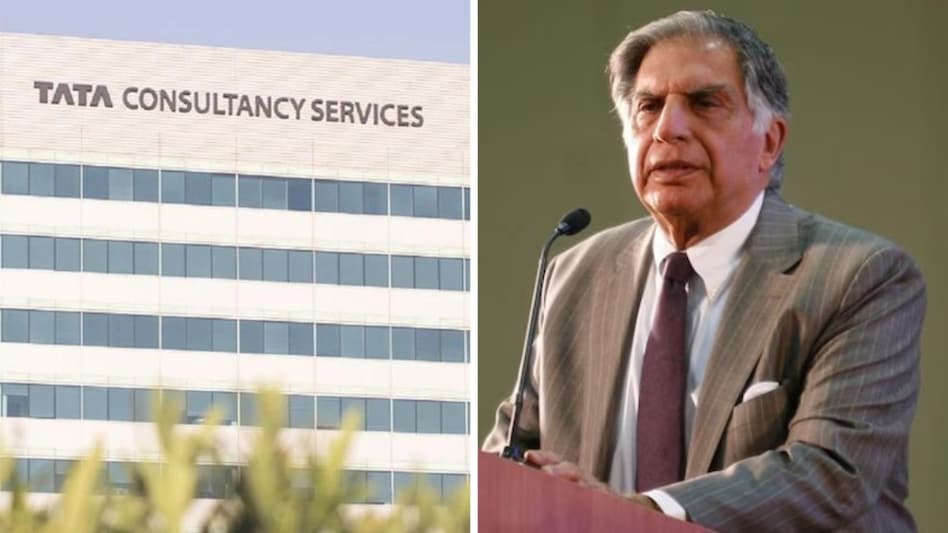

'Ratan Tata wanted higher share for retail investors': Tata veteran's new book reveals inside story of TCS IPO

In his new book Doing the Right Thing: Learnings from Ratan Tata, Tata Group veteran Harish Bhat recounts how Ratan Tata got upset over the low share for retail investors in the TCS IPO

- Nov 27, 2025,

- Updated Nov 27, 2025 3:34 PM IST

Ratan Tata did not just want to be legally right - he wanted to be morally right. He consistently promoted 'fairness' in whatever the Tata Group did. Ever since he took charge of the conglomerate in 1991, several of his decisions reflected the principles he followed while making them.

At the core of the veteran industrialist's choices was the belief that no one should be 'harmed' or 'treated unfairly'. One such untold story has now been revealed in a new book, involving Ratan Tata's demand for higher allocation for retail investors during the TCS IPO.

In his new book Doing the Right Thing: Learnings from Ratan Tata, Tata Group veteran Harish Bhat recounts how the listing of TCS - one of the most challenging decisions for Tata - tested his insistence on fairness. TCS began in 1968 as a computer division of Tata Sons and remained fully owned by the parent for the next three decades.

By the 1990s, TCS had emerged as one of the group's top-performing companies. And by then, private estimates put the valuation of the company at close to Rs 1 lakh crore. The key question that emerged in the late 1990s was whether Tata Sons should list TCS on the stock exchange.

The book notes that many opposed the idea, but Ratan Tata pushed for it for a few reasons - "one of the most important being that the listing would permit TCS to reward its employees with stock options" and it "would also help Tata Sons raise funds to modernise other Tata companies."

Ishaat Hussain, former director of Tata Sons, worked closely with Ratan Tata and Noshir Soonawala on the process. It was decided that Tata Sons would offer around 14 per cent of TCS's equity shares to the public, and that these shares would be listed on the NSE and the BSE.

In 2004, Tata Sons moved ahead with the IPO. But as Bhat writes, the offering came with several complexities, and Ishaat told him that Tata had to evaluate innumerable options before finalising the structure. The issue opened on 29 July 2004 - the 100th birth anniversary of JRD Tata - and closed on 5 August 2004. JRD had co-founded TCS.

Ishaat recalled a hectic week of roadshows to market the public issue. Eventually, he and Ratan Tata met bankers at the Taj Hotel's Chambers in Mumbai to decide the allocation and pricing of shares.

The IPO had been oversubscribed several times. The interest from retail investors had been spectacular, Bhat records. In fact, the issue was oversubscribed by retail investors alone. However, when the matter of allocation of shares came up, it was highlighted to Ratan Tata that as per the rules then in place, around 65 per cent of all shares had to be allocated to institutional (QIB) and non-institutional (HNI) investors. This restricted the retail quota to less than 40%. This meant small investors would receive only a fraction of what they applied for, while institutional investors would secure their full, much larger allocations.

"When Ratan Tata heard about this, he became visibly upset," Bhat writes. "He said that this was very unfair to the small investor. In fact, he wanted as many shares of TCS as possible to be owned by the common man, not by elite wealthy investors or by institutions alone."

Ishaat recalled that "Ratan Tata said he was ashamed to be party to an allotment pattern that was blatantly unfair." Tata expressed his concern to SEBI and asked Ishaat Hussain to raise the issue in the right fora. Hussain, then a member of SEBI's primary markets committee, took it up, but investment bankers put up their own arguments for why the high institutional quota was required. Eventually, the quotas remained unchanged for the TCS IPO, "much to Ratan Tata's intense dissatisfaction."

However, Ratan Tata ultimately made the key call on pricing.

After the share allocation discussions, the matter of pricing came up. The public issue had gone through the book-building process, within a range of Rs 750 to Rs 900. As the issue had been oversubscribed, and many investors had bid at the top, Ishaat recommended that the issue be priced at Rs 900, the top end of the range. "I was doing my job as the CFO of Tata Sons," Ishaat tells the author, "and my job was to maximise value for Tata Sons."

Ratan Tata, however, disagreed. He thought that the fair thing to do would be to price the issue at much less than Rs 900, thus providing a benefit for shareholders, and in particular for small retail investors. According to the book, he turned to Ishaat and told him, "Let us leave something on the table for the investors. Let us not try to maximise value only for ourselves."

After Ratan Tata's advice, the issue was priced at Rs 850 per share. As a result, Tata Sons had to forgo some part of the amount that it could have raised from the offer had it decided to price it at the top end. Ishaat tells the author that this was Ratan Tata's way of being fair to all the major stakeholders in the offer, "rather than trying to extract the highest value for only the seller".

The TCS IPO is among several little-known stories Bhat narrates in his book, which traces Ratan Tata's early life, career, and leadership during the era of economic liberalisation and thereafter.

Bhat, who has served at the Tata Group for 38 years and is currently on the boards of three Tata companies, also details how Ratan Tata, early in his tenure, worked to prevent any possibility of hostile takeovers, backed South Korean steel company POSCO's entry into India even though it would compete with Tata Steel, and opposed tariffs on Chinese solar products because he wanted Indian players to become competitive.

"Ratan Tata's desire to be fair in all his dealings was a very strong urge in him," Ishaat concludes. He recalls Ratan Tata telling him, "We must not only be seen to be doing the right thing, but we must be actually doing the right thing."

Ratan Tata did not just want to be legally right - he wanted to be morally right. He consistently promoted 'fairness' in whatever the Tata Group did. Ever since he took charge of the conglomerate in 1991, several of his decisions reflected the principles he followed while making them.

At the core of the veteran industrialist's choices was the belief that no one should be 'harmed' or 'treated unfairly'. One such untold story has now been revealed in a new book, involving Ratan Tata's demand for higher allocation for retail investors during the TCS IPO.

In his new book Doing the Right Thing: Learnings from Ratan Tata, Tata Group veteran Harish Bhat recounts how the listing of TCS - one of the most challenging decisions for Tata - tested his insistence on fairness. TCS began in 1968 as a computer division of Tata Sons and remained fully owned by the parent for the next three decades.

By the 1990s, TCS had emerged as one of the group's top-performing companies. And by then, private estimates put the valuation of the company at close to Rs 1 lakh crore. The key question that emerged in the late 1990s was whether Tata Sons should list TCS on the stock exchange.

The book notes that many opposed the idea, but Ratan Tata pushed for it for a few reasons - "one of the most important being that the listing would permit TCS to reward its employees with stock options" and it "would also help Tata Sons raise funds to modernise other Tata companies."

Ishaat Hussain, former director of Tata Sons, worked closely with Ratan Tata and Noshir Soonawala on the process. It was decided that Tata Sons would offer around 14 per cent of TCS's equity shares to the public, and that these shares would be listed on the NSE and the BSE.

In 2004, Tata Sons moved ahead with the IPO. But as Bhat writes, the offering came with several complexities, and Ishaat told him that Tata had to evaluate innumerable options before finalising the structure. The issue opened on 29 July 2004 - the 100th birth anniversary of JRD Tata - and closed on 5 August 2004. JRD had co-founded TCS.

Ishaat recalled a hectic week of roadshows to market the public issue. Eventually, he and Ratan Tata met bankers at the Taj Hotel's Chambers in Mumbai to decide the allocation and pricing of shares.

The IPO had been oversubscribed several times. The interest from retail investors had been spectacular, Bhat records. In fact, the issue was oversubscribed by retail investors alone. However, when the matter of allocation of shares came up, it was highlighted to Ratan Tata that as per the rules then in place, around 65 per cent of all shares had to be allocated to institutional (QIB) and non-institutional (HNI) investors. This restricted the retail quota to less than 40%. This meant small investors would receive only a fraction of what they applied for, while institutional investors would secure their full, much larger allocations.

"When Ratan Tata heard about this, he became visibly upset," Bhat writes. "He said that this was very unfair to the small investor. In fact, he wanted as many shares of TCS as possible to be owned by the common man, not by elite wealthy investors or by institutions alone."

Ishaat recalled that "Ratan Tata said he was ashamed to be party to an allotment pattern that was blatantly unfair." Tata expressed his concern to SEBI and asked Ishaat Hussain to raise the issue in the right fora. Hussain, then a member of SEBI's primary markets committee, took it up, but investment bankers put up their own arguments for why the high institutional quota was required. Eventually, the quotas remained unchanged for the TCS IPO, "much to Ratan Tata's intense dissatisfaction."

However, Ratan Tata ultimately made the key call on pricing.

After the share allocation discussions, the matter of pricing came up. The public issue had gone through the book-building process, within a range of Rs 750 to Rs 900. As the issue had been oversubscribed, and many investors had bid at the top, Ishaat recommended that the issue be priced at Rs 900, the top end of the range. "I was doing my job as the CFO of Tata Sons," Ishaat tells the author, "and my job was to maximise value for Tata Sons."

Ratan Tata, however, disagreed. He thought that the fair thing to do would be to price the issue at much less than Rs 900, thus providing a benefit for shareholders, and in particular for small retail investors. According to the book, he turned to Ishaat and told him, "Let us leave something on the table for the investors. Let us not try to maximise value only for ourselves."

After Ratan Tata's advice, the issue was priced at Rs 850 per share. As a result, Tata Sons had to forgo some part of the amount that it could have raised from the offer had it decided to price it at the top end. Ishaat tells the author that this was Ratan Tata's way of being fair to all the major stakeholders in the offer, "rather than trying to extract the highest value for only the seller".

The TCS IPO is among several little-known stories Bhat narrates in his book, which traces Ratan Tata's early life, career, and leadership during the era of economic liberalisation and thereafter.

Bhat, who has served at the Tata Group for 38 years and is currently on the boards of three Tata companies, also details how Ratan Tata, early in his tenure, worked to prevent any possibility of hostile takeovers, backed South Korean steel company POSCO's entry into India even though it would compete with Tata Steel, and opposed tariffs on Chinese solar products because he wanted Indian players to become competitive.

"Ratan Tata's desire to be fair in all his dealings was a very strong urge in him," Ishaat concludes. He recalls Ratan Tata telling him, "We must not only be seen to be doing the right thing, but we must be actually doing the right thing."