Japan’s Cold Test: Why believers plunge into ice before sunrise

Before dawn in Tokyo, worshippers plunge into ice at a Shinto shrine, enduring Kanchu Misogi—an extreme New Year ritual of purification, endurance, and communal faith.

- Jan 13, 2026,

- Updated Jan 13, 2026 3:47 PM IST

- 1/9

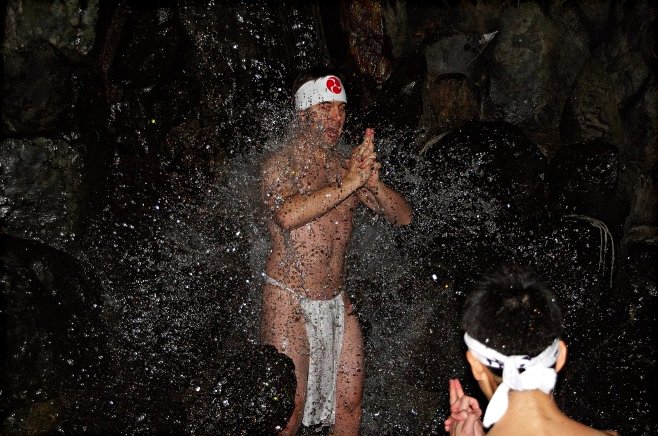

Before sunrise on New Year’s morning, while Tokyo’s apartments stay dark and quiet, bodies gather at Teppuzu Inari Shrine for an ordeal that rejects comfort outright. White-clad participants step into ice-choked water, turning devotion into something visible, physical, and almost defiant against the cold.

- 2/9

Kanchu Misogi doesn’t ease believers into reflection—it jolts them awake. Shinto priests describe the icy plunge as a reset button for the mind, where breath shortens, muscles rebel, and awareness sharpens to a single, urgent point: survival through focus and faith.

- 3/9

This isn’t punishment; it’s calibration. In Shinto thought, impurity comes from everyday life itself—stress, grief, exhaustion. Scholars note that extreme cold compresses attention so completely that participants experience a rare psychological clarity, something meditation alone rarely achieves.

- 4/9

What looks solitary is anything but. Participants shout encouragement, spectators cheer, and suffering becomes collective. Sociologists studying modern ritual argue that such shared hardship restores social bonds weakened by digital isolation, transforming pain into a brief but powerful form of unity.

- 5/9

Drums thrum, flutes pierce the winter air, and voices chant the name of Haraedo-no-Okami, the goddess of purification. The soundscape is deliberate—research on ritual music shows rhythm helps synchronize breathing and heart rate, subtly steadying bodies against shock.

- 6/9

The plunge lasts minutes, not seconds, but not long enough to cause harm. Organizers carefully control water depth and timing, blending ancient practice with modern risk awareness. Experts on ritual survival note that boundaries, not recklessness, preserve meaning.

- 7/9

Once private, the ritual now draws worshipers nationwide. Demand has grown so intense that registration often closes early. Cultural historians see this as evidence that ancient rites aren’t fading—they’re being rediscovered by younger generations searching for something tangible.

- 8/9

Though Japan’s emperor, Emperor Naruhito, holds a symbolic Shinto role, Kanchu Misogi remains fiercely local. Its power lies not in national spectacle, but in small shrines where belief is practiced, not performed for cameras.

- 9/9

Participants emerge shaking, skin steaming, faces calm. Many describe gratitude, humility, even joy. Psychologists call it “earned renewal”—the sense that starting the year with chosen discomfort reframes future hardship as survivable, even meaningful.