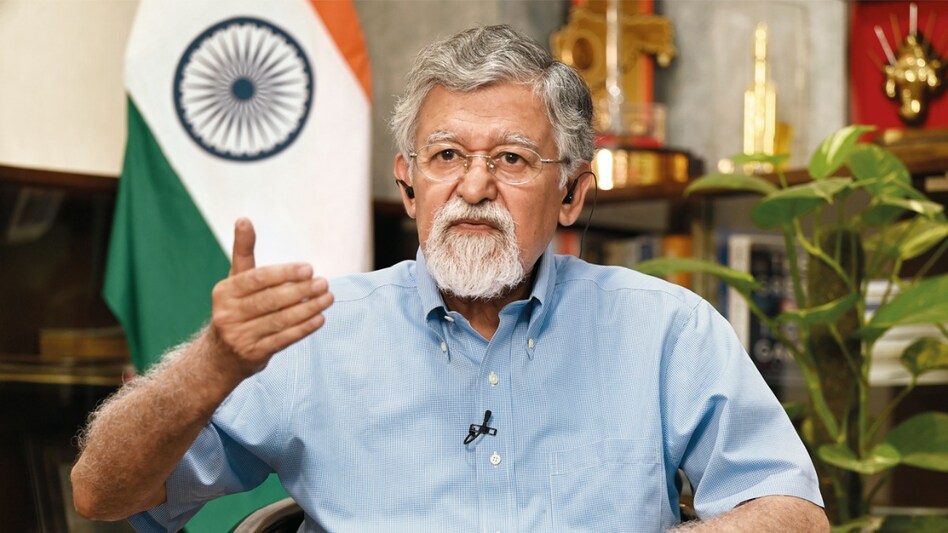

Cut through the jungle of controls: NITI Aayog member Arvind Virmani

Arvind Virmani, member of the NITI Aayog, on reforms and charging up India's growth

- Aug 9, 2025,

- Updated Aug 9, 2025 6:23 PM IST

As India prepares to speed up economic growth to meet the Viksit Bharat dream by 2047, one question crops up quite often: What is to be done? That’s a question 76-year-old economist Arvind Virmani, member of the NITI Aayog, has tackled at different junctures of India’s development journey. In an interview to BT, he talks about the areas that receive lesser attention in conversations about reforms but which are equally vital to ensure that growth meets ambitions. Edited excerpts:

- Unlimited access to Business Today website

- Exclusive insights on Corporate India's working, every quarter

- Access to our special editions, features, and priceless archives

- Get front-seat access to events such as BT Best Banks, Best CEOs and Mindrush

As India prepares to speed up economic growth to meet the Viksit Bharat dream by 2047, one question crops up quite often: What is to be done? That’s a question 76-year-old economist Arvind Virmani, member of the NITI Aayog, has tackled at different junctures of India’s development journey. In an interview to BT, he talks about the areas that receive lesser attention in conversations about reforms but which are equally vital to ensure that growth meets ambitions. Edited excerpts:

Q: What would be the top two or three areas on which we need to work to reach Viksit Bharat status?

A: Let me start with things that are less talked about. I would point to three things that I learnt and investigated over the last two-and-a-half years at the NITI Aayog. The first is what we could call the quality of learning and teaching. Statistics show that enrolment rates are 100% or thereabouts. The completion rates of various levels of schooling are very high, but learning tests show that we are very far behind where we need to be. So, in per capita terms, we are more or less in sync with other such countries. But if we want to become an upper middle-income country in 10 years, and a higher income country in 25 years, we must rapidly improve the quality of learning and teaching in schools.

The second is the skilling system. All the data that I have looked at shows that we are pretty far behind. So, not only do we have to catch up to the level where we should be, we must raise it to the Viksit level. And third, is local infrastructure. When we talk about urban infrastructure, we are talking about households in cities or towns, but the quality of the infrastructure in the legacy industrial estates is pathetic. A huge amount of work needs to be done on local infrastructure, just the basics like roads, cleanliness, sanitation, sewage, etc. And the problem in India is even when you put up something new, sustainability is critical.

Q: Should this improvement in local infrastructure remain confined only to the industrial estates, or should the approach of the states and local bodies be to have all areas reach a certain standard?

A: What I said is that even if there was an improvement in urban infrastructure, I am afraid the industrial estates would get left behind. When you are talking about a town, you can’t just look at the industrial estate. But when you are improving the town, whether it is Tier III or IV, please do not forget the industrial area. Somehow, we take it for granted that these areas can look after themselves. They cannot look after public infrastructure. That must be provided by the local and state authorities. And it is generally neglected.

Q: What are your thoughts on labour reforms in the medium and long term?

A: Labour is on the concurrent list, so there’s a role for both the national and state levels. Just the numbers first, the reasonable projections I’ve seen suggest an average of seven to eight million new entrants to the labour force every year over the next decade or two. We know that the four labour codes were passed by Parliament. The idea is that all the state governments make the relevant rules so that there’s uniformity. However, just because there is a national law, it does not stop any state from having a similar or even better law. Hopefully, some of the more progressive or advanced states can lead the way. It’s really a political issue. It’s important since large and foreign firms are very scared of what they consider to be a relatively disorganised labour market compared to the ASEAN countries, for example, where they have made large investments in setting up supply chains. I would urge states that want to promote supply chains to make these changes, because it reassures large companies that want to expand from 100 to 300, or 3,000 or 10,000 employees.

Q: Given the fact that land availability overall and contiguous pieces of land for industrial development is cited as an issue, what needs to be done?

A: Again, land is a state subject. So, firstly, we should note that different states have different land use laws, and some of this has been reviewed in the last Economic Survey. What we are trying to do at the central level is to bring cross-fertilisation of ideas to look at states that have better, more flexible land use laws, whether it’s for converting rural land to industrial use, or restrictions on the height of buildings, etc. If we want to encourage those who are going to generate economic activity, employment, this is an issue that needs to be solved. Different areas and industries have different solutions and so the intent is to nudge the states to see what is best for them and change it. Again, from my discussion with international companies, what they need is large tracts of land. It doesn’t always have to be contiguous, but definitely in the same city. It comes down to the recognition by the states that industry would be good for them, that you need to attract them to grow because they will generate jobs, higher wages, and employment.

Q: What needs to be done to take deregulation forward?

A: Legal reforms have been going on for a decade or so and certainly we have made a lot of progress. But as an academic who’s worked on these issues for a long time, I call it a jungle of controls that was built in our socialist period, from Independence to 1980. And it looks like an endless process, but it is not. One of the things that I have proposed in a working paper is using artificial intelligence (AI) to reform laws, rules, regulations, and forms. We’ve tried a lot and some of those efforts are succeeding. But AI could be a way to cut through the thicket to see where the overlaps are, where things can be simplified. Once you train an expert system to understand the law, it can be used to drastically simplify it too. I agree with those who say that there is still a lot of room to improve things. Adopting such a radical idea may take time, but I’m sure it’ll happen one day.

Q: Is it time to have some sort of automatic expiry date for laws?

A: I think we should restrict sunset clauses to economic laws, but I think that would be a good idea because things change a lot. We all know how rapidly the world is evolving. Right now, there’s so much uncertainty. Some of that is just short term. The point being, the economy is changing, people are changing. It isn’t a bad idea to say that a law will expire unless there’s a relook at a specified point. It’s like an alarm clock. Of course, that’s not a panacea.

Q: What needs to be done in terms of the agriculture sector?

A: What we do have to think of are overlaps. Take for example fertilisers. I remember 30, 40 years ago, we all thought that we needed more intensive use of fertilisers. But that approach has gotten to a point now where it is harmful. Then, we used to say that farmers must invest more. But if they are putting it in tube wells where the groundwater level is being depleted faster than it is being replenished, as it is in some parts of India, that’s a big problem. It’s part of the wider point I made that things have changed, but we tend to get stuck in a policy that may have been very good 50 years ago, but not anymore. Water is getting polluted, land is getting polluted, groundwater is getting exhausted… We need to change the policy. When there are major changes like that, you need to incentivise it, otherwise it won’t happen. But unfortunately, these are political issues, not in the electoral sense, but they are community political issues. I should also mention that for at least 30 years we have been talking about diversification to animal husbandry, fishery, etc. Yet, it is a very slow process. Now, some states, fortunately, that did switch their strategy to emphasise more on horticulture or fisheries grew very fast. Propagating these positive cases will hopefully induce other states to follow. But again, agriculture is a state subject, except for interstate trade. And, really, that is one of the issues. I think the Centre must keep nudging states to reform.

Q: What are the things that you believe states should be tackling?

A: One of the areas to look at is electricity. There’s a cross-subsidy in terms of electricity pricing. All distribution is in states’ control. They tax electric supply to industry and use that to subsidise consumers. All an economist like me can do is to make the point that instead of giving the direct subsidy, reduce the tax, price electricity according to the cost of production rather than levying a much higher rate for industry. You will get more jobs, you will get more economic activity, which will benefit the population, and that will raise demand and consumption. This is an area where I’m thinking of conducting a study to demonstrate the effects higher prices have. It’s an indirect effect. On the other hand, people can directly see their cost of electricity through the subsidy. Again, it is very difficult convincing the public that they’ll be better off five years from now.

The connectivity to transport infrastructure depends on states. All the finances come from the state, so really the state must decide that this is an important issue. There’s one more thing linked to my point on skilling. We have so many schemes, but this must be implemented at the local level. There are national and state training institutions. What we need is a proper tripartite effort, the government as a coordinator and information provider at the local level, not at the state or national level.

I should mention that at the NITI Aayog we are building an index that will help guide the states. The index will cover all the issues highlighted here, but indices by their very nature are mechanical. It still gives a measure that we hope will nudge states to address these issues.

@szarabi