‘It is ours too’: Pakistan reintroduces Sanskrit, charts courses on Gita, Mahabharata

The four-credit Sanskrit course, launched at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), is the first formal reintroduction of the language in Pakistan since 1947. The programme grew out of a short-term weekend workshop that unexpectedly drew strong interest from students and faculty.

- Dec 13, 2025,

- Updated Dec 13, 2025 8:46 PM IST

In a move that has surprised many across South Asia, Pakistan has begun reintroducing Sanskrit into its university curriculum, more than seven decades after Partition, signalling a renewed academic interest in the region’s ancient intellectual traditions. The initiative, led by a top private university in Lahore, also includes plans to eventually offer structured studies on the Bhagavad Gita and the Mahabharata.

The revival marks a rare moment of engagement with a classical language that once formed the backbone of philosophical, literary and scientific thought across the subcontinent, including areas that today lie within Pakistan.

A return after 1947

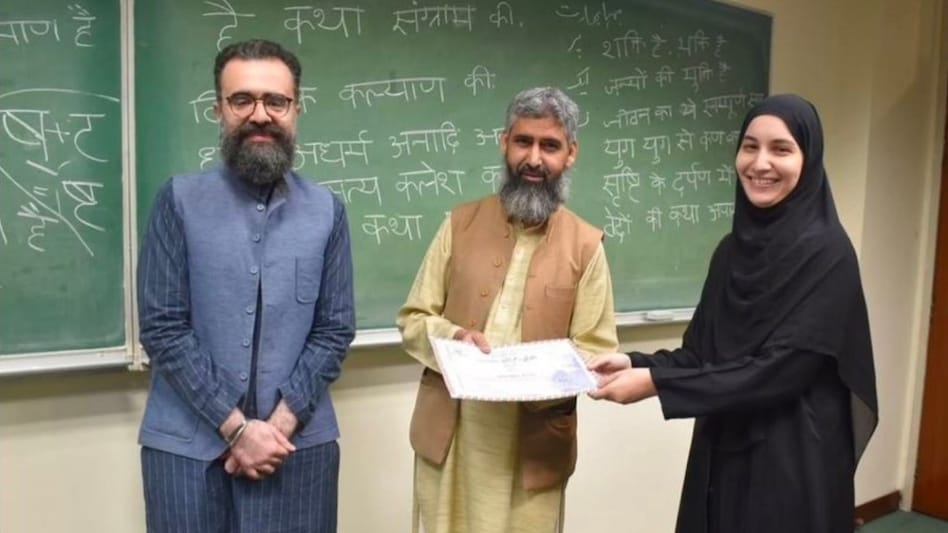

The four-credit Sanskrit course, launched at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), is the first formal reintroduction of the language in Pakistan since 1947. The programme grew out of a short-term weekend workshop that unexpectedly drew strong interest from students and faculty, prompting the university to expand it into a full academic offering.

University officials and faculty members stress that the move is academic and cultural rather than religious, aimed at reclaiming a shared heritage that predates modern political boundaries.

“Sanskrit is not ‘foreign’ to this land,” a faculty member associated with the programme said. “It shaped languages, literature and ways of thinking in this region. Studying it helps us better understand our own past.”

Gita, Mahabharata on the roadmap

Beyond language instruction, the university has indicated plans to introduce courses focused on classical Sanskrit texts, including the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita. These would be taught as part of literature, philosophy and history studies, rather than devotional texts.

Academics involved say the long-term goal is to develop home-grown scholars capable of reading and interpreting these works in the original language, something that has been largely absent in Pakistan’s higher education ecosystem.

Some faculty members believe that within a decade, Pakistan could have specialists trained locally in Sanskrit literature — an area currently dominated by scholars abroad despite the presence of extensive manuscript collections in the country.

Untapped manuscripts

Pakistan is home to thousands of Sanskrit manuscripts, particularly in libraries such as Punjab University’s collection, many of which remain under-researched. Scholars argue that the lack of Sanskrit education has prevented local academics from engaging directly with these texts, leaving a significant part of regional history unexplored.

Students enrolled in the course are also being introduced to links between Sanskrit and modern South Asian languages, including Punjabi and Urdu, highlighting linguistic continuities often overlooked in mainstream narratives.

While the initiative has been welcomed by academics and students interested in classical studies, it has also sparked debate on social media, reflecting broader sensitivities around identity, religion and history in Pakistan.

Supporters argue that the programme represents a confidence in plural intellectual traditions, while critics question its relevance. University authorities, however, maintain that classical languages are studied worldwide for their civilisational value, and Sanskrit should be no exception.

In a move that has surprised many across South Asia, Pakistan has begun reintroducing Sanskrit into its university curriculum, more than seven decades after Partition, signalling a renewed academic interest in the region’s ancient intellectual traditions. The initiative, led by a top private university in Lahore, also includes plans to eventually offer structured studies on the Bhagavad Gita and the Mahabharata.

The revival marks a rare moment of engagement with a classical language that once formed the backbone of philosophical, literary and scientific thought across the subcontinent, including areas that today lie within Pakistan.

A return after 1947

The four-credit Sanskrit course, launched at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), is the first formal reintroduction of the language in Pakistan since 1947. The programme grew out of a short-term weekend workshop that unexpectedly drew strong interest from students and faculty, prompting the university to expand it into a full academic offering.

University officials and faculty members stress that the move is academic and cultural rather than religious, aimed at reclaiming a shared heritage that predates modern political boundaries.

“Sanskrit is not ‘foreign’ to this land,” a faculty member associated with the programme said. “It shaped languages, literature and ways of thinking in this region. Studying it helps us better understand our own past.”

Gita, Mahabharata on the roadmap

Beyond language instruction, the university has indicated plans to introduce courses focused on classical Sanskrit texts, including the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita. These would be taught as part of literature, philosophy and history studies, rather than devotional texts.

Academics involved say the long-term goal is to develop home-grown scholars capable of reading and interpreting these works in the original language, something that has been largely absent in Pakistan’s higher education ecosystem.

Some faculty members believe that within a decade, Pakistan could have specialists trained locally in Sanskrit literature — an area currently dominated by scholars abroad despite the presence of extensive manuscript collections in the country.

Untapped manuscripts

Pakistan is home to thousands of Sanskrit manuscripts, particularly in libraries such as Punjab University’s collection, many of which remain under-researched. Scholars argue that the lack of Sanskrit education has prevented local academics from engaging directly with these texts, leaving a significant part of regional history unexplored.

Students enrolled in the course are also being introduced to links between Sanskrit and modern South Asian languages, including Punjabi and Urdu, highlighting linguistic continuities often overlooked in mainstream narratives.

While the initiative has been welcomed by academics and students interested in classical studies, it has also sparked debate on social media, reflecting broader sensitivities around identity, religion and history in Pakistan.

Supporters argue that the programme represents a confidence in plural intellectual traditions, while critics question its relevance. University authorities, however, maintain that classical languages are studied worldwide for their civilisational value, and Sanskrit should be no exception.