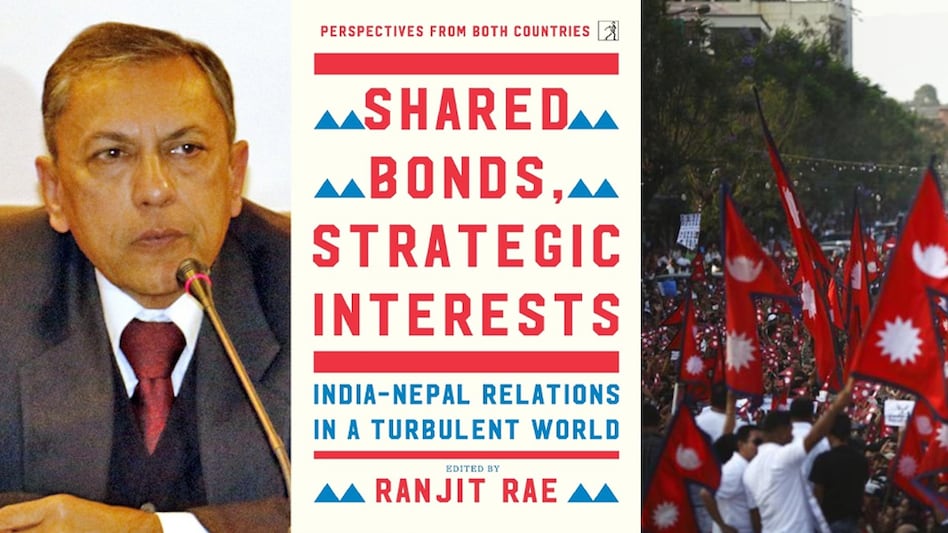

Ranjit Rae, former Indian ambassador to Nepal, has come out with a new book - Shared Bonds, Strategic Interests: India–Nepal Relations in a Turbulent World

Ranjit Rae, former Indian ambassador to Nepal, has come out with a new book - Shared Bonds, Strategic Interests: India–Nepal Relations in a Turbulent World

Ranjit Rae, former Indian ambassador to Nepal, has come out with a new book - Shared Bonds, Strategic Interests: India–Nepal Relations in a Turbulent World

Ranjit Rae, former Indian ambassador to Nepal, has come out with a new book - Shared Bonds, Strategic Interests: India–Nepal Relations in a Turbulent WorldThough a relatively small country, Nepal's significance for New Delhi is of Himalayan scale, given its geography and its role as a critical buffer between India and China.

Ranjit Rae, former Indian ambassador to Nepal, captures the importance of the Himalayan nation in his newly edited book - 'Shared Bonds, Strategic Interests'.

"Whenever Nepal is vulnerable, third forces and inimical external elements begin to play," Rae says in an exclusive interview with Business Today. "We have seen that - the hijack of IC 814 in 1999 - and there have been similar incidents where terrorists either fled to Nepal or used Nepal for activities inimical to our security."

The book examines Nepal's recent political churn, including the Gen Z–led protests that contributed to the fall of the KP Oli government. But can monarchy ever make a comeback? He says it is "very unlikely," but if things deteriorate, "politics can take unpredictable turns."

Rae also makes a case for New Delhi to consider some exceptions to allow the resumption of Nepali recruitment into the Gorkha regiments - a century-old practice that was paused by Kathmandu after India introduced the Agniveer scheme.

Edited excerpts

Why is Nepal important for India, and why should New Delhi care about this Himalayan nation in the context of wider geopolitics?

India is a subcontinent. It wants to be a global power. It has aspirations for a permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council. India has aspirations to be a rapidly growing and developed economy. We talk about Viksit Bharat - how do you achieve all these things? Apart from investments and economic growth, India needs a neighbourhood that is peaceful. A neighbourhood that is in turmoil will absorb India's energies - you will be putting out fires everywhere.

So the neighbourhood is absolutely critical for India's own growth, development, regional and global role, and political & geostrategic role.

We have a very unique relationship between India and Nepal. We have open borders, document-free travel between the two countries. We have very similar cultures, languages, and family relationships. Also, Nepal is situated in a very sensitive geopolitical area. Eight of the highest Himalayan peaks are in Nepal. Fifty per cent of the water that comes into the Ganga is from rivers that flow from Nepal into India.

The neighbourhood is critical - and within that, Nepal has a very unique place because of its geographical location, because of the cultural closeness between our two countries, and because it is sitting in the lap of the Himalayas.

From a security perspective, Nepal is often described as a crucial buffer between India and China. How significant is Nepal in India's strategic calculus?

Nepal is very important from a security perspective, and China - whether we like it or not - always becomes a factor in the relationship because of its geographical location and fluctuation in the India-China relationship.

Whenever Nepal is vulnerable, third forces, inimical elements, and external elements begin to play. And we have seen that - the hijack of IC 814 in 1999 - and there have been similar incidents where terrorists would either run away to Nepal or use Nepal for activities inimical to our security. So, it becomes a very important security relationship.

You argue in your book that the Gen-Z protests in Nepal were largely homegrown and that tensions had been building for some time. What were the underlying developments that we missed here in India?

I don't think we missed it. We had sensed for quite some time that there was a lot of discontentment.

First, one-third of Nepal's population works abroad. Thousands of young people are leaving the country to look for work. There are no jobs at home. People are complaining about why there is no economic growth. They see what is happening abroad, how rapidly other countries are growing, and so they question - why is it that Nepal is not growing?

Second is the corruption issue. There have been so many economic scandals in Nepal, and these are happening with impunity. Top political leaders are involved. This has led to a lot of resentment.

Now, the instant trigger for the protest was the banning of social media apps. I was listening to an interview of one of the Gen-Z leaders, and he said, 'Look, during COVID time, our lives revolved around social media. All our issues were discussed on social media platforms.' So that became like a village panchayat where people sit and chat in the evenings and talk about things.

But the government thought that it could ban these apps. Actually, they had been asking these apps to register with the local authorities and have some local person stationed in Nepal with whom the government could be interacting in case things have to be taken down, etc. These are big companies. So some of them ignored it and because they ignored it and the deadline passed, the government banned it, not realising the implications.

This also implies the extent to which the government and the leadership were completely separated from the grassroots-level mood. There was a big gap between what the political leadership was doing and what the young were thinking.

Some argue that anti-India feelings started after the 2015 blockade by New Delhi. What exactly had happened?

I take a slightly longer perspective.

I don't think the anti-India feeling started in 2015. Of course, the events of 2015 again revived this, but this anti-India feeling has been there for a long time, and there are many reasons.

One, because of the asymmetry in the relationship. Nepal is surrounded by India on three sides, and India looms very large in the Nepalese psyche. It's a very strong presence in Nepal - and in the north, they have the Himalayas, which are some sort of a barrier. With China, they don't have this kind of cultural thing.

Two, the cultural similarity. Nepal always feels that when Indians say, 'Oh, everything is the same - culture, language, religion', then the question of identity arises. This is another factor that leads to resentment. This is something that we have to be very sensitive to.

The third thing is history. In 1960, King Mahendra abolished multi-party democracy in Nepal. The Government of India and Prime Minister Nehru were very critical and said this was a royal coup. Because India was unhappy with him, the king turned to China. From then China's entry into Nepal became stronger.

As New Delhi was unhappy with the king, he tried to get the support of the Hindu elements in India and declared Nepal a Hindu Rashtra. This happened only in 1962. He tried to consolidate his own supporters - the hill elite, the Brahmins and Kshatriyas of the hills. These were the traditional rulers of Nepal. So he started hill nationalism. He gave a very famous slogan - one country, one language, one religion, and one king.

As a result, the people of the plains - the Madhesis - felt totally alienated. The Madhesis are people like the people in UP and Bihar. The king conflated the Madhesis with Indians.

The Nepali Congress leaders were in exile in India because the king had abolished their government. So, in order to neutralise these elements, he started encouraging the leftist forces in Nepal. Interestingly, the communists and the royalists were aligned on this question of anti-India nationalism.

Even in 2015, it was Prime Minister KP Oli who headed the Communist Party of Nepal. He picked up this anti-India nationalism and became a leader in his own country. So, it is a very lazy analysis to say that anti-India feeling started only in 2015. Of course, 2015 contributed to it, but this is something that the royalist elements and the communist elements in Nepal have always fanned. This is the schooling of these elements, and this will remain. It's not going to go away. This is something we have to live with and see how we can manage.

When K P Oli stepped down, a section of people wanted the monarchy to return. Do you really see any possibility of the return of the king?

Right now, things are in a big flux in Nepal. Nobody really knows what is going to happen, and there seems to be some discontent with the Constitution of 2015. At that time, they said it was the best in the world, much better than India's. India had only "noted" the Constitution, and the Nepalese were very unhappy about that.

We had been saying that please take everybody along, listen to the concerns of others who feel left out, accommodate them, and there will be peace. Today, they are saying many things need to change.

People are saying the proportional representation system should go. People are unhappy with federalism dividing Nepal into seven provinces. They say it is too expensive. But these provisions of the Constitution came, because of the Maoist insurgency and the Madhesi agitation. These people who felt discriminated against wanted a greater share and role in the resources of the state.

So, reopening these elements can be quite dicey. We don't know what implications this will have. The core features of the Constitution - republicanism, federalism, multi-party democracy - if these are reopened, we don't know what could happen.

My own sense is that it is very unlikely that people will feel that the monarchy is the answer. But there are elements in Nepal who feel that the king was a symbol of our identity, and we have lost that. These elements in the last elections could only get five per cent of the overall vote. They are not very significant, but in a situation of flux, if things deteriorate, politics can take unpredictable turns.

You write that Nepal's earlier experience with monarchy was not particularly positive for India. Even if the king were to return, would it necessarily improve India-Nepal relations?

Absolutely not. The king was responsible for the anti-India nationalism in Nepal. Historically, the king is the one who reached out to China. The king is the one who talked about Chinese membership of SAARC at the Dhaka Summit in 2005. It is the king who brought in the concept that Nepal is a zone of peace, equidistant from China and India.

From the Indian perspective, the monarchy has not been very helpful in the past. Of course, there are elements in India that say Nepal should be a Hindu Rashtra. But they forget that it became a Hindu Rashtra only in 1962.

In Nepal, what they say is that the king is an avatar of Vishnu. If Nepal is to be a Hindu Rashtra, then it is natural that an avatar of Vishnu will rule that Rashtra. So the king and the Hindu Rashtra, in a sense, are very closely interconnected.

These are issues for the Nepalese people to decide. India should not get involved because these are very controversial issues within Nepal itself.

Your book highlights the historical role of Nepali citizens in the Indian Army's Gorkha regiments. Since the introduction of the Agniveer scheme, Nepal has stopped its citizens from joining. Should India consider making an exception for Nepali citizens?

Absolutely, yes. This unique feature where the Indian Army used to recruit Nepalese for its Gorkha regiments is not new. This has been going on for more than 200 years. The Gorkha soldiers have fought in every Indian war and have shed their blood. They are a very important element of our army, and if you speak to any Gorkha officer in India, he will talk about the bravery of these soldiers and how important they are for the army. They have won Param Vir Chakras, Mahavir Chakras, and so many awards.

So this is a very important aspect of the relationship - not only the military relationship but the overall relationship between India and Nepal. We have 1,25,000 Nepalis - we call them Bhutpurva Gorkha soldiers - who are in Nepal, and they get pensions from India. The pension itself is about three to four per cent of Nepal's GDP. This is a very important element.

We should see whether the Agniveer scheme needs to be liberalised for these Nepalese Gorkhas or if an exception can be made. This is something that we need to discuss with the Nepalese. We should find out from the Nepalese why it is that they are not joining the Indian Army anymore. What they tell us is that it is mainly an issue of pensions and the very short tenure.

They feel that so many soldiers will come back after four years, and these are people well-trained in weapons. This might create security problems in Nepal. They say, 'Look, we had a very violent Maoist insurgency for ten years. Seventeen thousand people were killed. Now, if these soldiers come back, how will they reintegrate? These people can use modern weapons.'

At the very least, whatever facilities we give to Indian Agniveers, we must give to the Nepalese as well. Like in India, we are saying that after four years, those who are not permanently recruited will be given preference for CAPF (Central Armed Police Forces). We should give the same preferences to the Nepalese.

There was some talk that instead of four years, the government might increase the period to eight years. That would be a positive thing. This is something that we need to discuss with the Nepalese side. We should do everything we can to ensure that this tradition of Nepalese joining the Gorkha regiment is maintained.