When you go shopping for vegetables, wouldn’t you be surprised if prices changed every few minutes? You would be irritated and wary and you may well decide

to switch markets and seek a wholesale market where the rates were more stable. You would certainly become a more discerning and calculating shopper if you had to buy your veggies under such conditions.

Of course, vegetable prices don’t fluctuate with minute-to-minute frequency. But stock prices do. They change continuously and the direction is random and unpredictable. On an average day, the Sensex swings around by over 2%. Individual stocks may move by over 3%. This continuous, unpredictable motion frightens many wannabe investors. Oddly, those who remain committed to share market investing don’t necessarily become more discerning or calculating shoppers.

Behavioural psychologists have puzzled over the fact that the same person, who will sensibly buy potatoes only when the price is low, will buy stocks only when the price is high. Common sense says that this is idiotic — yet it is the popular course of action. To cap it, people who buy high often get spooked by volatility into selling when prices are low. What is volatility? It is the rapid change in prices — in either direction. It is inherent to stock markets — share prices can change astonishingly in a very short time.

Many investors find this so scary that they exit the market forever. Others stay in the game but suffer insomnia every time prices twitch. Volatility is not necessarily a bad thing. When it brings prices down, it offers smart shoppers bargains.

When it sends prices spiking up, it gives bargain-hunters bigger returns. It is a fact of life in equity markets — and it is uncontrollable. To understand the double-edged implications, consider a practical case. On 31 January 2007, two investors buy Tata Steel. On 30 April 2007, they both sell, punching in “at-market” orders.

One gets a return of 16.35% while the other gets a return of -13.9%. Why the difference? Well, on 31 January, Tata Steel made a high of Rs 539 and a low of Rs 461 and on 30 April, it had a high-low range of Rs 536.5 and Rs 464. One investor bought at the high on 31 January and sold at the low on 30 April while the other bought at the low and sold at the high. One was a victim of volatility; the other was a gainer from it. Neither investor had control over his returns.

A very smart, very committed, full-time trader may be able to finetune trades to exploit such volatile situations to the hilt. But as an investor, you should not even try to time price swings. The difference in attitude between a trader and an investor is not always understood. Think of the trader as the shorthaul commuter who hangs out of a train trying to get to the next station in a hurry. He takes risks, suffers discomfort and frets every time the train slows down. The investor in contrast, is a long-distance passenger who books his reservation in advance and sleeps in comfort as the train chugs along until it reaches its destination.

Of course, you should be aware of the impact volatility can have on returns. Returns from equity can never be accurately predicted. Volatility creates inevitable error margins and that should be incorporated into your financial planning. The best action in the face of volatility is often inaction. Ignore it when seeking long-term returns. Once you have picked a good business, work out the maximum price you are prepared to pay, based on the intrinsic value of the business and its growth prospects.

As the two doyens of long-term investment suggest, you should buy only when a share is available below your estimate of intrinsic value, thus offering a margin of safety. Once you have bought, ignore price swings. You should be prepared to hold forever. Sell only if you think the long-term prospects are deteriorating or the share price is too high. This buy-and-hold method is how successful investors make their fortunes.

Good businesses can offer great returns over decades, sometimes over centuries. Tata Steel has just celebrated its first century. ITC is almost as old. So are Hindustan Unilever and Colgate. Even a relatively young company like Reliance Industries has been around for more than 30 years and sunrise businesses like Dr Reddy's and Infosys got listed over 10 years ago.

If a business is founded on sound principles, run efficiently, and moves with the times, there is no reason it would ever cease to make profits. General Electric, the creation of inventor Thomas Alva Edison, was one of the original 30 stocks in the first-ever stock index, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (1907). A hundred years later, GE is still one of the world’s premier companies and still part of the DJIA. Of course, the larger a business becomes, the more difficult it is to inject growth. Nevertheless, it will continue to be a cash cow. When you identify a business which promises long-term payback, it makes sense to buy another chunk every time the price is right.

Having said that, one shouldn’t be completely passive during a volatile phase. Only, don’t sell—buy. Volatility and market crashes can be useful to long-term investors. High volatility causes nervousness, which often leads to dips in share prices — an opportunity to buy. Stock traders try to time price. An investor must time valuation. He buys every time the valuation is lower than intrinsic value. How does one decide intrinsic value? There are many methods — we have outlined one of the most successful in our indigenising of what Graham and Buffett would pick today in the Indian markets.

In the broadest terms, any profitable business generates future cash flows. We can assign a current value (called a net present value or NPV) to such future cash flows. For example, if the interest rate is 10%, and somebody offers to pay Rs 110 say 12 months down the line, the current value of that Rs 110 is roughly Rs 100. Similarly if you will receive a return of Rs 121 two years down the line, the NPV is close to Rs 100.

Once you roughly predict future cash flows and assign a current value, you have an intrinsic valuation for a business. Of course, such predictions can never be accurate. But you don’t need pinpoint accuracy with this approach, provided you maintain a margin of safety and pay less than fair value. During sudden crashes and corrections and longterm bear markets, stocks often trade well below their intrinsic value. That gives you the margin of safety.

This might seem a little hit-and-miss. But it works better than most alternate methods. Sound investment methods outlast cycles and fads and generate profits across decades. We took a look at some of the most famous Indian companies over the considerable timeframe of 16 years, starting with the new economic policy of 1991.

The return for buy-and-hold investment strategies over this period is excellent. Even the Sensex itself, which is a basket of 30 businesses, generated a return of 1,433% absolute over this period. Individual Sensex components generated a lot more (RIL at 5,090%). The returns for investors who increased their stake on every price dip rather than simply buying and holding are even better.

According to our calculations, if you bought during the crash periods of greatest uncertainty, your average annualised return would be more than 20%. In contrast, the safety-first approach of heading for debt instruments during volatile periods ended up offering far lower returns.

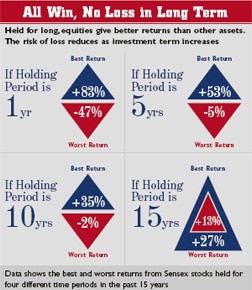

In the very long term, volatility ceases to matter much — over decades, equities generate higher returns than less volatile instruments and is actually less risky than apparently safe instruments. This is something most investors don’t realise. That is why investors chase quick returns from the share market and look for long-term safety in debt.

The best way to handle investing is, in fact, to have exactly the opposite attitude. In the short run, debt is safe and offers assured returns. In the long run, inflation erodes its value. In contrast, good businesses offer variable short-term returns.

Many extraneous factors come into play and influence short-term price moves. But since they generate consistent long-term profits, they offer consistent long-term returns. As Graham once said, “In the short-term, the stock market is like a voting machine. In the long run, it is like a weighing machine.”

Short-term share price fluctuations are influenced by fads and fashions. In the long term, only the good businesses survive. There is a simple way to judge this. Investors who let their fears overwhelm their good sense are the ones who lose when the market gets freaky. Of course, there will be exceptions, but your chances are excellent that riding out the bad times will reward your patience.

Sometimes it might take longer to recover, but for as far back as we have data, the market has usually recovered within 5-10 years. A rolling average gives you average annualised returns for the period ending with the listed year, so the 15-year rolling return for 31 March 2007 covers April 1, 1992, through March 31, 1993. It represents what your return would have been had you sold at the end of that period.

A lot of factors can influence shortterm stock movements and many of these have little to do with sustainable profits. For example, the current volatility is being influenced by a crisis in subprime mortgages. This led to a drop in the price of a drug company like Ranbaxy! The only connection is liquidity. As Ajit Dayal points out, the subprime crisis reduced liquidity and so the share price of Ranbaxy fell, even though its profits are unaffected by the US mortgage defaults.

Political uncertainty also creates wonderful buying opportunities because it triggers bear markets. For example, between 1996 and 1999, India had as many as three prime ministers and a lameduck government. The political uncertainty led to a bear market where the Sensex suffered losses for three successive years. Many people lost heart but some who saw this as a long-term investment opportunity reaped huge returns in the next decade.

Again in 2004, there was a brief period of uncertainty after the NDA government was voted out. In May 2004, the Sensex dropped 22% within eight days. In the next three years, it rose 188%. The change in government didn’t cause deterioration in the economic environment.

Crisis = opportunity. It requires faith and discipline to invest according to this mantra. It requires even more discipline to avoid high-flying stocks when day traders are crowing over fantastic returns. Nobody said it was easy being a long-term investor. But if you want to generate stable longterm returns, you can’t do it without equity exposure. And in equities, you will face volatility. Only by displaying common sense in the face of volatility can you be an uncommonly successful investor.

With Narayan Krishnamurthy