Bharat forge chairman and Managing Director Baba Kalyani summed up the key takeaway from Operation Sindoor at the recently held Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) annual business summit. “Executed with strategic clarity and precise coordination, it showcased not only the operational brilliance of the Indian armed forces but also the growing strength of India’s indigenous defence manufacturing ecosystem.”

The operations were a defining moment for India’s fast-growing defence manufacturing sector. The prospect of more orders prompted some to announce capital expenditure plans. “We have to take responsibility to build equipment fast so that we can provide our armed forces much more than what they have today and what they need in future,” Kalyani added. Pune-based Bharat Forge is one of India’s leading private sector defence manufacturers.

Almost on cue, Dassault Aviation and Tata Advanced Systems announced four production transfer agreements to make fuselage of the Rafale fighter jet at a new facility in Hyderabad. The partnership is a significant achievement for India’s aim of becoming a major defence manufacturing hub. It marks a significant first for the €6.2 billion French aerospace company as the Hyderabad facility, to be set up by Tata Advanced Systems, will be the first factory outside France to manufacture Rafale fuselage. The partnership has the potential to boost the country’s defence and aerospace ecosystem and encourage other biggies to explore manufacturing tie-ups with Indian companies. At present, indigenous manufacturing is primarily driven by partnerships between government-run Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and industry.

Self-Reliance Goal

Operation Sindoor signalled that the growing confidence of armed forces in indigenous products would lower India’s defence imports. India was the second-largest arms importer from 2020 to 2024; it accounted for 8.3% of global defence imports. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) data show that Russia, France and Israel were the biggest suppliers and together accounted for about 82% of India’s global spending on arms during the period. The dependence on Russia has halved since 2010-14 to 36% as India stepped up purchases from France, Israel and the United States, besides boosting domestic production. SIPRI notes a 9.3% drop in India’s arms imports between 2015-19 and 2020-24, “partly as the result of India’s increasing ability to design and produce its own weapons.”

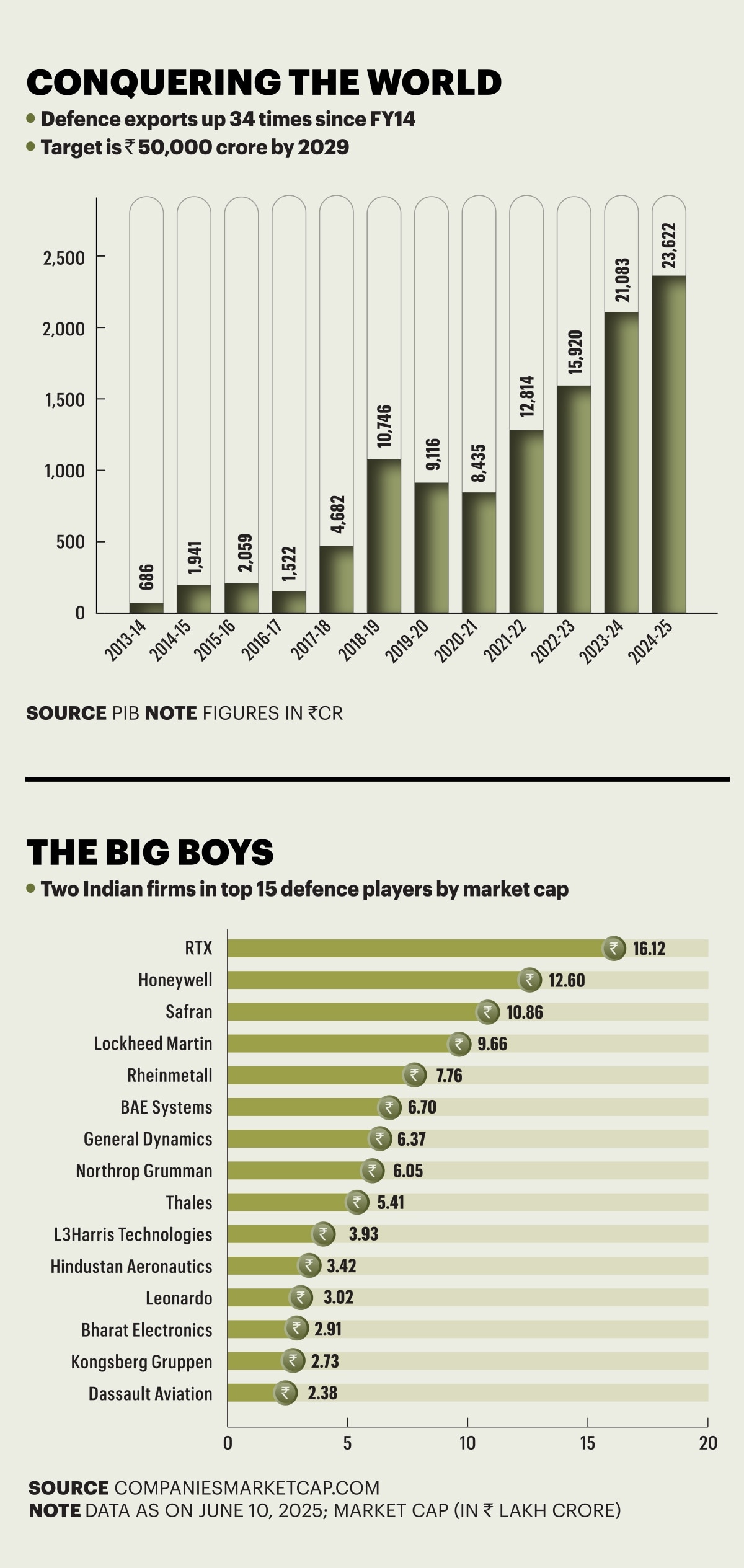

Nonetheless, the overall defence spending may rise faster given the increased hostility in India’s neighbourhood, the volatile geopolitical situation and the changing nature of warfare. India was the fifth-largest spender ($86.1 billion) on arms in 2024. As this number rises in the coming years, local sourcing will rise. Initiatives such as Make in India, Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan and easier regulations have put India on the path of becoming a major defence manufacturer. Already, indigenous defence production has grown 174% from `46,429 crore in FY15 to over `1.27 lakh crore in FY24, government data show. This reduced the share of imports in defence purchases to about 35%. Parallelly, exports jumped about 34 times, from Rs 686 crore in FY14 to `23,662 crore in FY25. India’s exports to about 100 countries include bulletproof jackets, Dornier aircraft, Chetak helicopters, fast interceptor boats and lightweight torpedoes. About 65% of the products exported were made by the private sector. The trend is expected to continue. “Boeing has quadrupled defence imports from India from $250 million to $1 billion in the last four years, and given the manufacturing capabilities of Indian defence players, we believe this can easily cross $2 billion over the next few years,” says Antique Stock Broking in a recent report. In the near term, the government expects domestic production to rise to `3 lakh crore and exports to `50,000 crore by 2029.

Ground For Growth

The government has facilitated growth of the private sector in defence not only by giving it more orders but also providing a level-playing field. It has amended procurement policies to increase buying from the private sector and taken steps to improve the ease of doing business. The Defence Acquisition Procedure of 2000 provides specific reservations on orders up to `100 crore per year for MSMEs. Further, it is preferring competitive bidding, where both private and public companies can compete, over the cost-plus procurement model, which was based on nominations, mostly to public sector enterprises. For instance, it allowed the private sector to bid for manufacturing the advanced medium combat aircraft (AMCA) instead of handing the project to Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd. The AMCA, a fifth-generation stealth fighter being developed by Aeronautical Development Agency, is more advanced than the Rafale jets. The first prototype is expected by 2027.

Role of R&D

The DRDO has also been instrumental in driving indigenisation in defence manufacturing. “The DRDO is sharing technology liberally with the private sector and entering into development-cum-production partnerships with them,” says S. Samuel C. Rajiv, research fellow at Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA). Such partnerships have led to the emergence of a vibrant ecosystem. At present, over 16,000 MSMEs make components, modules and subsystems for the 16 defence PSUs and more than 430 licensed defence companies. DRDO Chairman Samir V. Kamat has assured continued partnership with industry “to make India a leading R&D (research and development) country where people look to us for innovation in defence technology.”

However, the R&D on defence needs to rise. The government spends about 5% of the defence budget on R&D. This might rise to 10% in the next five years. The R&D spending of the private sector is abysmally low, and not just in defence. Some estimate that Indian industry spends less than 1% of its revenues on R&D. Society of Indian Defence Manufacturers (SIDM) President Rajinder Singh Bhatia acknowledges that self-reliance will require filling technology gaps and adopting the ‘whole of nation’ approach. . “While most of the gaps could be filled by domestic R&D, some others would require foreign technology partners,” he says. A Vision 2047 document published by the CII and KPMG recommends increasing R&D investment to 10-15% of the defence budget by 2032 with focus on AI, quantum computing and cyber defence.

Another reason R&D investments must go up is the changing character of warfare with rising use of unmanned vehicles and drones. “Although manufacturing is required, without the ability to design and develop, you will have systems that are not cutting-edge,” says DRDO’s Kamat. Holding intellectual property (IP) within the country is essential to become self-reliant, says SIDM’s Bhatia. “If the IP is within the country, while some portion of the supply chain may always be import dependent, you can always ensure what you want to do. If a certain item is not available, you can always develop an alternative supply source as long as critical technologies and IP are resting within the country.”

Dependence On World

The goals are laudable, but 100% indigenisation of manufacturing is unlikely, even if India acquires the technology and global manufacturers set up local production base. PwC India Managing Director (Aerospace and Defence) Vishal Kanwar says “the country will have to continue importing certain critical technologies, components and rare earth minerals.” India is estimated to have vast reserves of rare earth minerals but very little of that is produced or processed. China, with the largest known deposits of rare earths, is the dominant player.

Similarly, import of certain critical components will continue due to the nature of the supply chains. For example, the weakest link is propulsion system for warships, submarine and jets as India does not make gas turbines or jet engines. Even when co-development or co-production of engines begins, certain components will continue to be imported because global partners may not agree to complete transfer of technology.

For instance, GE Aerospace, which entered into an agreement with Hindustan Aeronautics in June 2023 for local production of F414 jet engines for the Indian Air Force’s Tejas, had shown willingness to transfer technology for up to 80% indigenisation. There is no indication when this project will go ahead. Hindustan Aeronautics has dismissed reports that the partnership is in trouble.

Despite global players’ reluctance to share technology with Indian partners, industry and analysts continue to be optimistic. “Transfer of technology gets only know-how and not know-why. There will be a natural reluctance to part with your golden goose. But the issue is how well we can leverage our national strength, our financial strength and our market size,” says SIDM’s Bhatia.

Building Scale

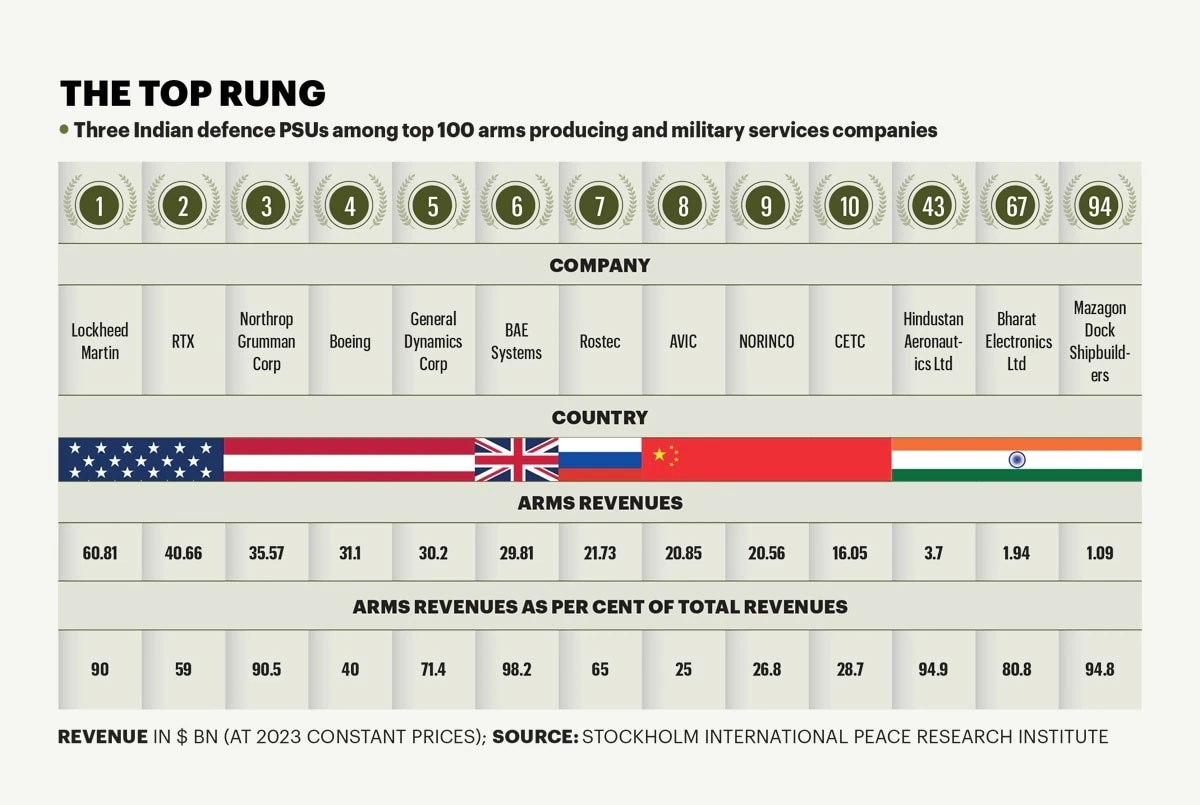

India’s defence PSUs have over the years gained size and scale. Hindustan Aeronautics, Bharat Electronics and Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders are among the world’s top 100 arms producing and military services companies, according to SIPRI rankings for 2023, published last December. Hindustan Aeronautics, with defence revenues of $3.7 billion, was at the 43rd place.

Conglomerates such as Tatas, Bharat Forge, L&T and the Mahindra Group, among the early starters from the private sector, have sizeable defence manufacturing operations. “Defence manufacturing is today where automotive manufacturing was in 2015,” says PwC’s Kanwar, who expects India to become a manufacturing hub by 2035 when the level of indigenisation rises to 80-85%. Each of these private sector companies has plans to expand and specialise in specific categories. “India needs to develop national champions for specific products,” says MP-IDSA’s Rajiv.

“While land and information & communications technology (ICT)-based segments are expected to witness increased private participation, the defence public sector undertakings would continue their dominance in naval, aerospace and armaments,” says Suprio Banerjee, vice president and co-group head at ratings agency ICRA. Companies in the ICT segment offer drone technologies, high-resolution imaging technology, electronic warfare technologies for receiving signals and jamming, aerial and under-water surveillance, avionics, satellite services and radars.

The Challenges

Scaling up is not easy. “The monopsony (only one buyer) nature of the sector and irregularity of orders are a deterrent to investors,” Nuvama Institutional Equities says in a note. “Lenders avoid funding unless a strong collateral is provided,” it says. Private sector companies often face working capital crunch as they do not get advances unlike the PSUs.

Order flows from the government are lumpy, and for continuous order book, manufacturers need to export. “Defence exports are and will always be an instrument of the nation’s foreign policy,” says SIDM’s Bhatia. It would therefore be always driven by national policy and support. Government support is necessary for India to become a major arms exporting nation, he adds. A report by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry has identified delays in getting export licences as a big challenge. “It takes three-six months to get export licences despite clear timelines for export clearances,” says the report.

Defence companies will also have to contend with shortage of skilled manpower as they grow rapidly. “The rapid evolution of military logistics, cybersecurity and advanced technologies demands a highly skilled workforce. Shortages in specialised personnel, including cybersecurity experts, logistics managers and AI specialists, create capability gaps in defence operations,” says a Niti Aayog working paper.

Jyoti Gupta, research analyst at Nirmal Bang, says data security can emerge as a big challenge. “As we move towards smart factories, embrace additive manufacturing and scale up AI infrastructure, ensuring data security is a strategic imperative,” she says. The Niti Aayog paper suggests a comprehensive Defence Cyber Security Framework with mandatory compliance standards.

As India seeks to become a manufacturing hub and a leading exporter, manufacturers should be able to procure components quickly to complete orders in time. The country will also have to invest heavily in R&D to keep up with the technological changes in warfare.

@tinaedwin