Ashok Jainani

Propelled by stimulus money and a tight supply of agricultural goods, India's inflation rate is rising at a breathtaking pace. The Wholesale Price Index (WPI) rose 4.8 per cent in November 2009. Based on this index, food inflation saw a rise of 18.2 per cent for the week ending 26 December. With the economy gaining traction, analysts do not foresee a respite from high prices this year.

Stock market proponents have long argued that if inflation reduces the purchase value of money, investing in stocks can protect against value erosion. In reality, there is no bigger lie than this. In an inflationary environment, people feel happy as asset prices, in general, rise. They mistakenly think that their wages and the value of their houses have gone up, whereas only the prices of daily essentials like bread and milk have risen.

While studying the impact of inflation on the stock market, we find that neither equity prices nor the issuing companies' return on capital have risen in tandem with the inflation index. According to conventional proposition, when inflation has led to a rise in the prices of raw materials and finished goods, stocks have benefited from the profits generated by companies. It is believed that companies with strong franchises have the capability to counter inflation by raising their selling prices without losing volumes.

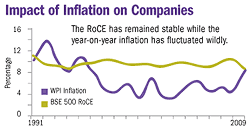

It supposes that a moderate rate of inflation allows companies to pass the increased costs to consumers and, thereby, earn increased profits, boosting return on investment. In a blow to such theories, the data over the past two decades does not show any close connection between inflation and stock market returns. The WPIbased annual average inflation has ranged between 3 per cent and 13 per cent from 1991 till March 2009, while the annual return on capital employed (RoCE) of the BSE 500 companies has remained stable between 9 per cent and 11 per cent.

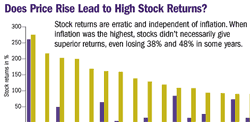

So, do stocks rise and fall in line with inflation? We studied the returns of two major indices—the Sensex and the US Dow Jones Industrial Average, as they represent a basket of very large and most liquid stocks in two different markets.

The annual average returns from the Sensex and the Dow Jones show no correlation with inflation over the past 20 years. The data, which encompasses periods of low and high inflation, shows no evidence that high inflation leads to higher, real equity returns. On the contrary, part of the data shows that low and stable inflation produces higher corporate earnings, which are again reflected in higher stock prices as investors are willing to pay a premium for superior growth. Conversely, high inflation robs the corporates' ability to pass on the increased cost to consumers and, hence, they take a hit on profitability, which leads to lower stock prices. When the inflation rate was the highest, Indian stocks lost a whopping 38-48 per cent.

Two things are certain: inflation and market fluctuation. The prices of things, be it food or stocks, will change. Even under the price mechanism administered by the government, the retail cost of petrol per litre today is 20 times of what it was two decades ago. Surprisingly, and audaciously, not only the government, but the economists and market commentators too tell us that they have brought inflation under control.

Ashok Jainani is Vice-President, Research & Market Strategy, Khandwala Securities