On the face of it, Shabbir Patel is a financial planner’s dream come true. He saves nearly 50% of his income. Invests in equities only through mutual funds and that too via systematic investment plans. Never rolls over the balance on his credit card. Spends only about a fourth of his salary on himself and shoulders half the household expenses of his family comprising his parents and himself. Wow.

Patel, 26, has already won half the battle by investing regularly. He will realise the significance of this habit in the years to come. Money saved in the first few years of working life contributes the maximum to overall wealth. The earlier one starts, the wealthier he is likely to be. Here’s the math. If someone invests Rs 5,000 a month for 30 years and earns 12% annualised returns, the Rs 18 lakh invested over the period would grow to Rs 1.75 crore at the end of 30 years. But knocking the first five years out would cut his wealth down by more than 46%. So, the Rs 3 lakh saved in the first five years contribute as much as Rs 80 lakh to the corpus of Rs 1.75 crore.

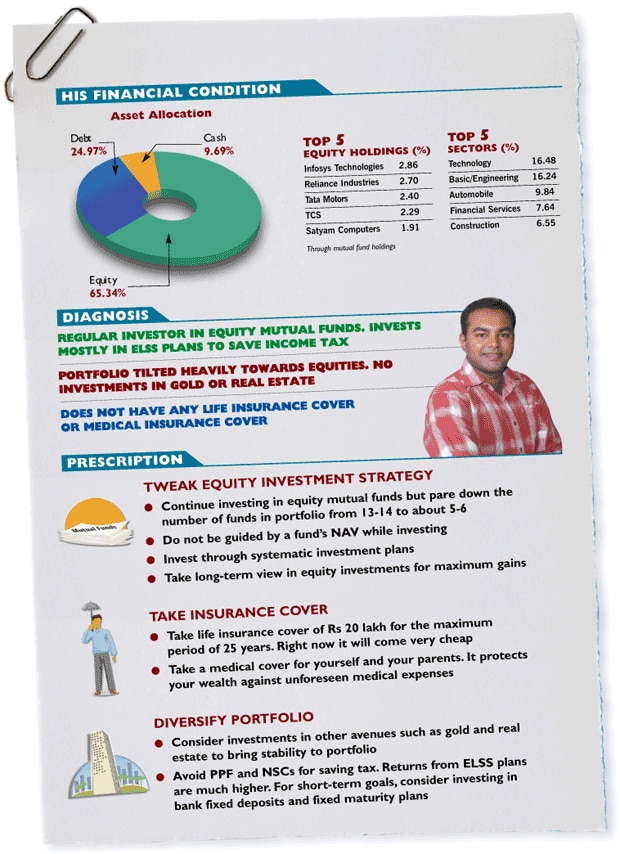

At the portfolio level, he is broadly moving in the right direction. About 77% of his assets are in equity funds, while the remaining 23% is in the rock solid safety of debt. It is an aggressive strategy but given that Patel has time by his side, he can afford to maintain a high equity allocation. Therefore, such an asset allocation is suitable.

But Patel’s selection of funds needs to be tweaked. His fund selection is based on mistaken beliefs. He commits the common mistake of assessing a fund’s prospects by looking at its NAV (net asset value).

The lower the NAV, the cheaper (and more attractive) the fund. Which also means that some of his investments haven’t grown as fast as they could. About 15 months ago, he put a lumpsum Rs 20,000 in Reliance Tax Saver “because the NAV was only around Rs 12.50”. The investment has yielded an annualised return of 13%.

Meanwhile, SBI Magnum Taxgain, which had an NAV of Rs 56—more than four times that of Reliance Tax Saver—has given an annualised return of over 27%. There is little scope to make changes because almost 90% of Patel’s mutual fund investments are in ELSS plans which have a threeyear lock in. What he can do is monitor his investments and focus only on outperforming funds.

Reliance Tax Saver accounts for 16% of Patel’s total investments in mutual funds. That is too high for a relatively new fund. The other tax plans chosen by him for future SIPs—Magnum Taxgain, HDFC Tax Saver, ICICI Prudential Tax Plan and Sundaram BNP Paribas Tax Saver—are among the best.

However, Patel could leave out Magnum Taxgain and spread his investments across the other three funds. Magnum Taxgain already accounts for nearly 25% of his portfolio, and concentration in a single fund is not advisable.

The other problem with Patel’s mutual fund investments is that there are too many schemes. He has some 13 funds in his portfolio, far too many for an individual to monitor. Ideally, one should have about 5-6 funds in his portfolio. He should avoid adding more funds.

One should go for a different fund only if it offers some unique proposition which is not fulfilled by existing well-performing funds, or if any of the funds goes into a rut and needs to be replaced. Otherwise, it is best to stick to the ones in the portfolio. Patel also needs to redefine his investment horizon. “I want to invest for the long term,” he says determinedly.

But his “long term” is as short as 12 months. He plans to get married in about a year’s time and wants to liquidate some of his fund holdings to foot the expenses. Patel needs to keep in mind that equities deliver high returns when kept for longer periods. When it comes to equity mutual funds, a one year horizon would be described as short term.

Long term is anything beyond five years. If Patel wants to withdraw money after a year, he will be better off if he invests in a fixed deposit or a fixed maturity plan (FMP). The income from FDs is clubbed with the income for the year and taxed accordingly. FMPs are more tax efficient because the income is treated as capital gains and gets indexation benefits. If the holding period is across three financial years, double indexation reduces the tax to almost zero.

Life insurance or medical cover does not find any place in Patel’s financial plan. This is a big loophole. He needs to take insurance cover as soon as possible. As far as life insurance is concerned, term cover is the cheapest and most efficient form of insurance. Sure, you don’t get any money back when the term ends. But then, neither are you forced to invest in low-yielding avenues through a money-back or endowment policy.

Patel is 26. At his age, a Rs 20-lakh term cover for 25 years would cost him about Rs 5,500 a year. It would be a good strategy to buy medical insurance cover for himself and his parents as well. With the cost of medical care going up, medical insurance is a good way of plugging unexpected leaks that spring up in household finances.

Patel’s investment portfolio is heavily tilted towards equities. Given his young age, this would yield rich dividends in the long term. But just for the sake of diversification, Patel could also consider investing in gold and real estate. These would lend stability to the portfolio.