Succession planning in the corporate world is evolving, and Dabur provides for an interesting case study. Dabur India Chairman Mohit Burman says, “The shift to professional, non-family succession was not a rejection of family legacy; it was a reimagining of the process.”

Burman’s observation sums up the philosophy that has guided one of India’s oldest consumer goods companies through its most radical transition.

The Burman family continues to hold significant ownership, but leadership has been entrusted to professional managers, supported by robust governance frameworks and independent board oversight. For Dabur, a fifth-generation family-led enterprise, ‘professionalisation’ was not about diluting the legacy but preserving it.

Burman explains that the journey began as early as the late 1990s. “The fourth-generation family members, after successfully running the business, decided to take a back seat and hand over management control to professionals. The strategic thrust came from the promoters. That was when we decided to hand over management control to professionals and the family took non-executive roles on the board.”

A similar shift is already visible across other marquee groups. Mahindra appointed Anish Shah as its first non-family CEO, Marico’s Harsh Mariwala entrusted leadership to Saugata Gupta, and Sona Comstar’s Late Sunjay Kapur ceded operations to professionals. Pharma majors Cipla and Dr Reddy’s have also embraced professional leadership, while Infosys pioneered the model years ago. Meanwhile, Asian Paints and Havells India, despite promoter ownership, have been professionally managed for years.

The guiding principle, Burman says, has always been that the organisation comes first. “We were among the first to realise that the promoters should provide a long-term vision to the company, and that professionals should manage the show efficiently,” Burman told Business Today, adding that the decision to hand over management control was taken in the best interest of Dabur.

It was also a conscious decision about future generations. “It was decided, way back in 1998, that none of the Burman family members would get an entry into Dabur.”

Burman admits the transition was not without its challenges. He recalls the difficulty of stepping back, especially in “attracting the right professionals to lead a business still largely perceived as family-run.” Yet, the move proved prescient. “Each member now manages their own enterprise, creating new legacies while the family continues to play a trusteeship role in preserving and growing Dabur as an institution.”

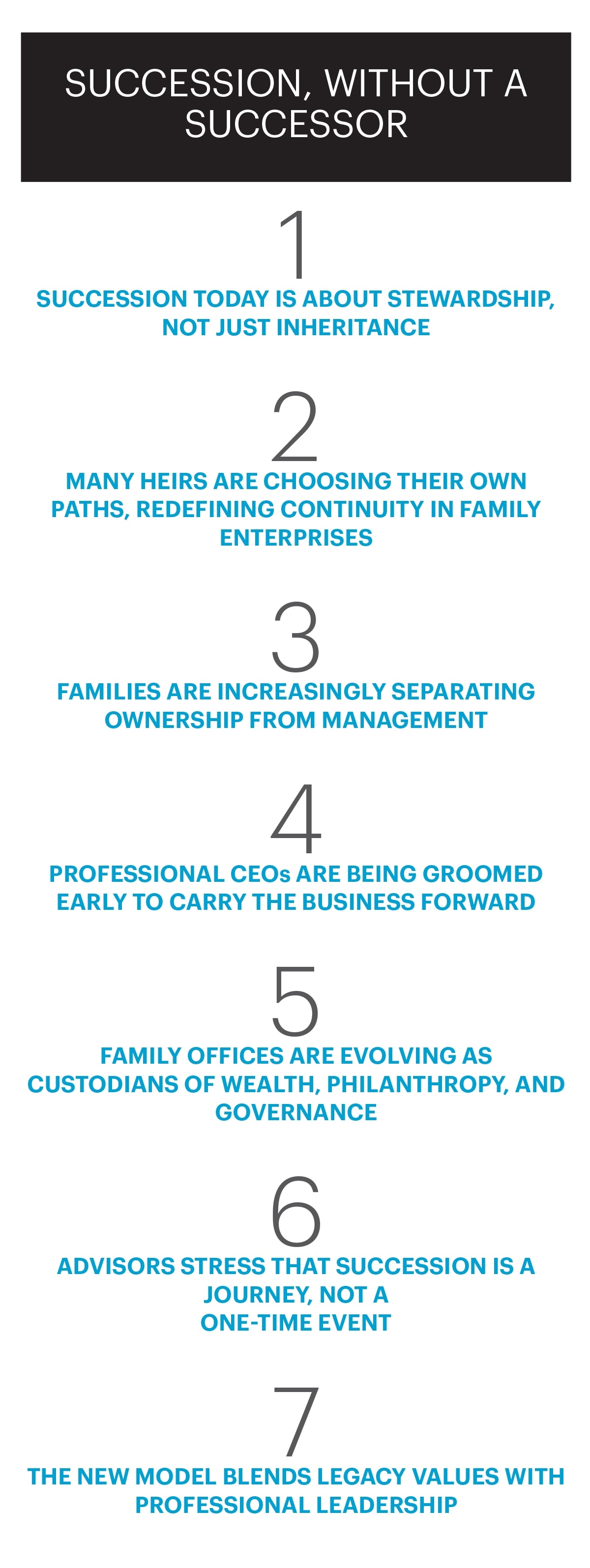

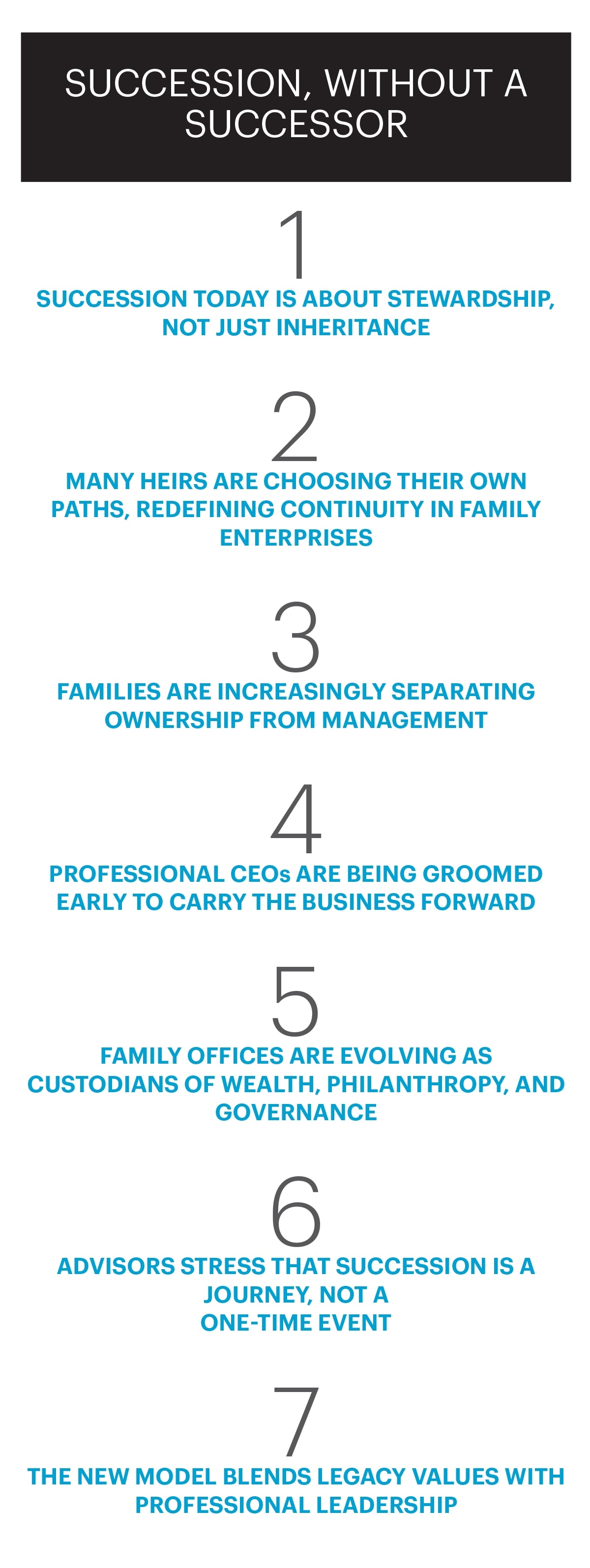

The Dabur story reflects a quiet revolution underway in India’s family businesses. Long seen as synonymous with dynastic succession, they are now redrawing the rules of continuity. According to HSBC’s report, Family-owned businesses in Asia: Harmony through succession planning, while 88% of entrepreneurs trust the next generation with family wealth, 45% don’t expect them to run the business. Only 7% of heirs, in fact, feel bound to take it up.

This shift is far from uniquely Indian. Around the world, leading family enterprises are choosing professional leadership to balance heritage with scale. British multinational venture capital conglomerate Virgin Group has been led since 2011 by non-family CEO Josh Bayliss, while Richard Branson and his family continue to provide vision and ownership. At LEGO, the Danish Kirk Kristiansen family continues to own the group, but the reins have passed to non-family chief executive Niels B Christiansen. In the US, Cargill, one of the country’s largest family-owned businesses, remains majority-owned by the Cargill-MacMillan family but is professionally run, with Brian Sikes serving as CEO and Board Chair.

REWIRING SUCCESSION

Industry watchers say the writing is clear: lineage is giving way to value (or talent from outside).

“The next generation is globally exposed, less interested in ‘running’ legacy firms, and more focused on ‘transforming’ their current businesses or creating new ventures through family offices,” says Sandeep Bhalla, Senior Partner & Head of Consulting, of global consulting firm Korn Ferry India.

Founders also recognise that scaling up and governance are best left to professional CEOs.

“For today’s heirs, legacy is less about holding the corner office and more about shaping the future through ownership, values, and vision,” Bhalla adds. He contends the key drivers for this shift include global exposure and new aspirations, with next-gen leaders, often educated abroad, being less tied to legacy firms and more drawn to entrepreneurship, venture capital, and future-focused sectors like climate, fintech, and digital innovation.

Founder pragmatism and governance pressures also play a role, as promoters acknowledge the complexity of scaling up and regulatory scrutiny, recognising that professional CEOs are better equipped to meet investor and compliance expectations.

For heirs, legacy is being redefined to lie in ownership, values, and shaping the future, with their focus on the transformation agenda, new ventures, funds, and innovation platforms, while professional CEOs take charge of running and growing the core business.

Younger members are professionalising family offices, channelling wealth into start-ups, alternative assets, and other investments. Much like in Singapore and South Korea, these offices are fast becoming centres of influence, innovation, and intergenerational stewardship.

Bhalla’s views find resonance with Raj Lakhotia, a seasoned professional in tax advisory, succession planning, and transaction advisory and Managing Partner at L A B H & Associates. “The reality is that many second-generation heirs are no longer tied to the traditional model of joining the family firm. A large proportion are settled abroad, and not keen on returning to run legacy businesses that they may see as conventional or slow-moving. Their aspirations are increasingly tech-driven, building start-ups, entering the digital economy, or pursuing careers in global corporations that promise structured five-day work weeks and the freedom of weekends, away from the intensity of family-run enterprises.”

Bhalla adds that this shift mirrors a broader social change. “The Indian social fabric is becoming more westernised, with younger generations prioritising personal fulfilment, lifestyle, and experiences over legacy obligations.” The mindset, he adds, has moved from ‘building for tomorrow’ to ‘living for today.’ At the same time, businesses themselves have grown far more complex, governed by stricter regulatory oversight, global competition, and investor scrutiny. This makes professional leadership not just a choice but often a necessity.

Building on this, Burman believes succession in Indian family businesses is not a one-size-fits-all story, but a case-by-case evolution. He says some next-gen leaders scale up legacy firms while others pursue start-ups or investments. A similar recognition of changing realities can be seen in the choices of other promoters. Harsh Mariwala exemplifies this shift by prioritising the organisation’s interest, choosing professional leadership over family succession at Marico, opting for Saugata Gupta instead of his son Rishabh as CEO.

Admitting to family unhappiness and social pressure, Mariwala, in a recent media interview, said, “People would ask, ‘How come you didn’t appoint your son?” Yet he believes the call was right: valuations rose, internal equations improved dramatically over time.

Mariwala said Marico also needed “a new set of thinking” and leadership capable of steering the company into its next phase.

SUCCESSION FRAMEWORK

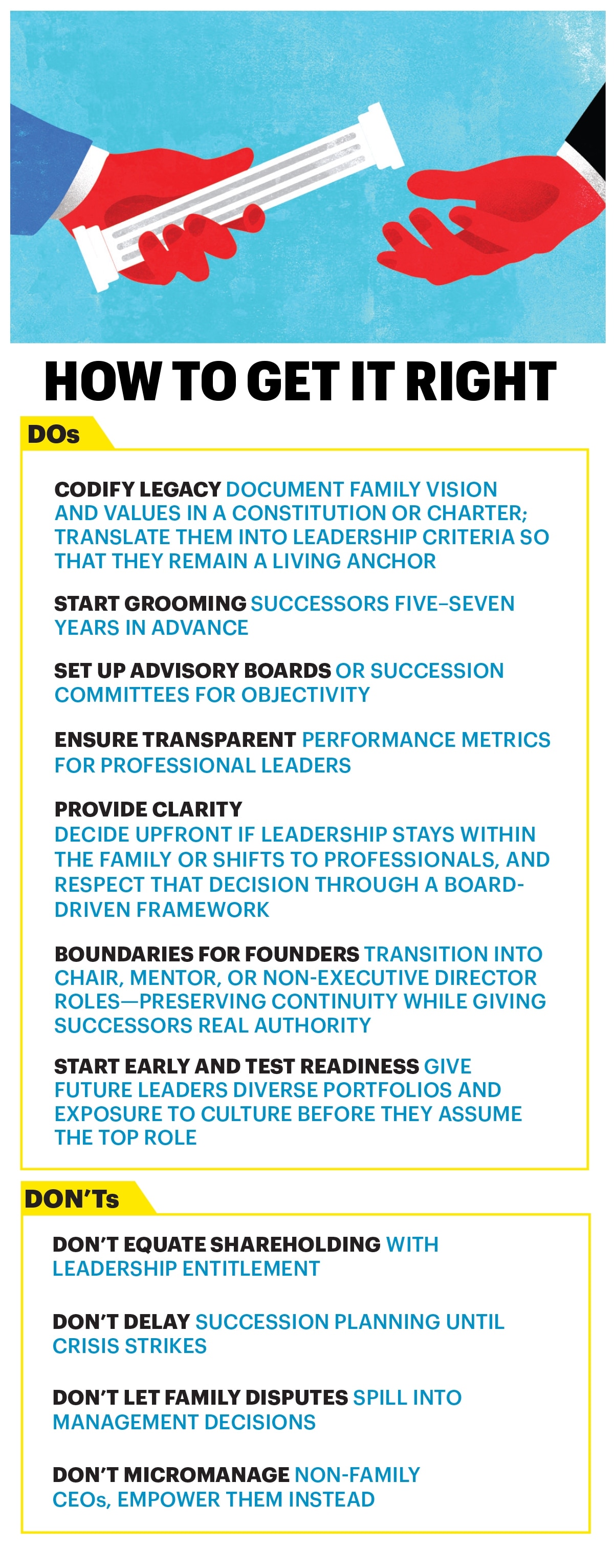

A well-designed succession framework creates dual continuity—values on one hand, structures on the other.

Lakhotia emphasises codifying a founder’s values in a family constitution and separating ownership, management, and oversight through structured governance. He advocates grooming successors early, setting up advisory boards, and empowering professional CEOs without micromanagement.

Dabur exemplifies this with its Family Council, ensuring strategic alignment and legacy continuity through regular, structured engagement.

Just as important, Lakhotia stresses, is resisting the temptation to micromanage non-family CEOs. “Empower them instead,” he says.

Bhalla, meanwhile, emphasises codification of legacy but goes further in underlining clarity and formalisation. He advocates a board-driven succession framework, overseen by the Nomination & Governance Committee, to ensure transparency and fairness. Founders, he adds, must also respect boundaries by transitioning into roles such as Chair, mentor, or Non-Executive Director.

Burman captures it best when he says succession is not about inheritance but about stewardship. “Treat the business and the family as two distinct institutions, each with its own space, respect, and governance.”

BALANCING LEGACY AND LEADERSHIP

Burman emphasises that succession at Dabur is not seen as a single moment but as a journey. Preparing a professional leader to take over requires a rigorous, multi-layered process rooted in foresight, capability mapping, and cultural alignment.

“Once the promoter family has decided to let a professional team manage day-to-day operations, it must step aside and allow them to run the show,” Burman maintains. The family, however, remains available to provide broad guidance or support if required.

The challenges of transitioning leadership without a clear family successor are often rooted in trust.

“Long-serving employees, customers, and partners have built deep trust with the family name and replacing that with a non-family professional requires deliberate credibility-building,” says Lakhotia.

Beyond that, risks of power vacuums or turf wars, within the family, among senior executives, or even in the promoter’s own mind, can emerge if boundaries are not clearly defined.

To prevent professional CEOs from being second-guessed or undermined, structured frameworks are essential: family values must be codified in a charter, shareholder alignment ensured, and legitimacy reinforced.

Succession, Lakhotia, echoing Burman, emphasises, should be seen as a journey rather than a one-time event. “Powers can be transferred gradually, early decisions hand-held, and outcomes evaluated before scaling responsibilities.”

Grooming and onboarding a non-family CEO is a process that requires constant handholding, structured exposure, and a gradual transfer of powers.

Lakhotia suggests exposing the CEO to founder values, family ethos, and organisational DNA through structured sessions, mentoring, and storytelling. In a landscape where tradition once dictated continuity, India’s family businesses are now crafting a new narrative—one that honours legacy while embracing change.