The conversation that began in the snow-capped Swiss Alps reached a crescendo in the desert metropolis of Dubai. From the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos to the World Governments Summit (WGS) in Dubai, one theme dominated every panel, every discussion, every conversation: artificial intelligence (AI) wasn’t just coming, it was here and the world was scrambling to understand what that meant.

At the World Governments Summit 2026, the urgency was palpable. This was no longer a speculative debate about the future. Real companies were seeing real disruption, markets were reacting with real panic and leaders were grappling with real questions about sovereignty, jobs and the future of human work itself.

Markets blink first

The market’s wake-up call came swiftly and brutally. When Anthropic unveiled its AI assistant Claude with new plug-ins for legal services, global equity markets trembled. Indian IT stocks crashed, with the Nifty IT index plunging over 7% in a single day. In the US, nearly $300 billion in market value vanished from software and financial data companies.

Tech Mahindra’s CEO Mohit Joshi watched the carnage unfold and called it what it was: hysteria.

“I certainly feel that it looks like a significant market overreaction,” Joshi told Business Today on the sidelines of the Dubai summit. “I do feel that this is a market overreaction to a very specific piece of news. It certainly appears to have been very widespread.”

But Joshi’s argument went beyond calming jittery investors. Speaking at a panel, he urged global leaders to think bigger, far bigger.

“If your total ambition for AI is to be able to, you know, get rid of a few contact centre jobs or to improve developer productivity, people are really missing the picture,” he said.

His vision? “The objective of AI, for instance, should be: how can we provide everybody a truly world-class healthcare service for $10 a month?”

AI as national power

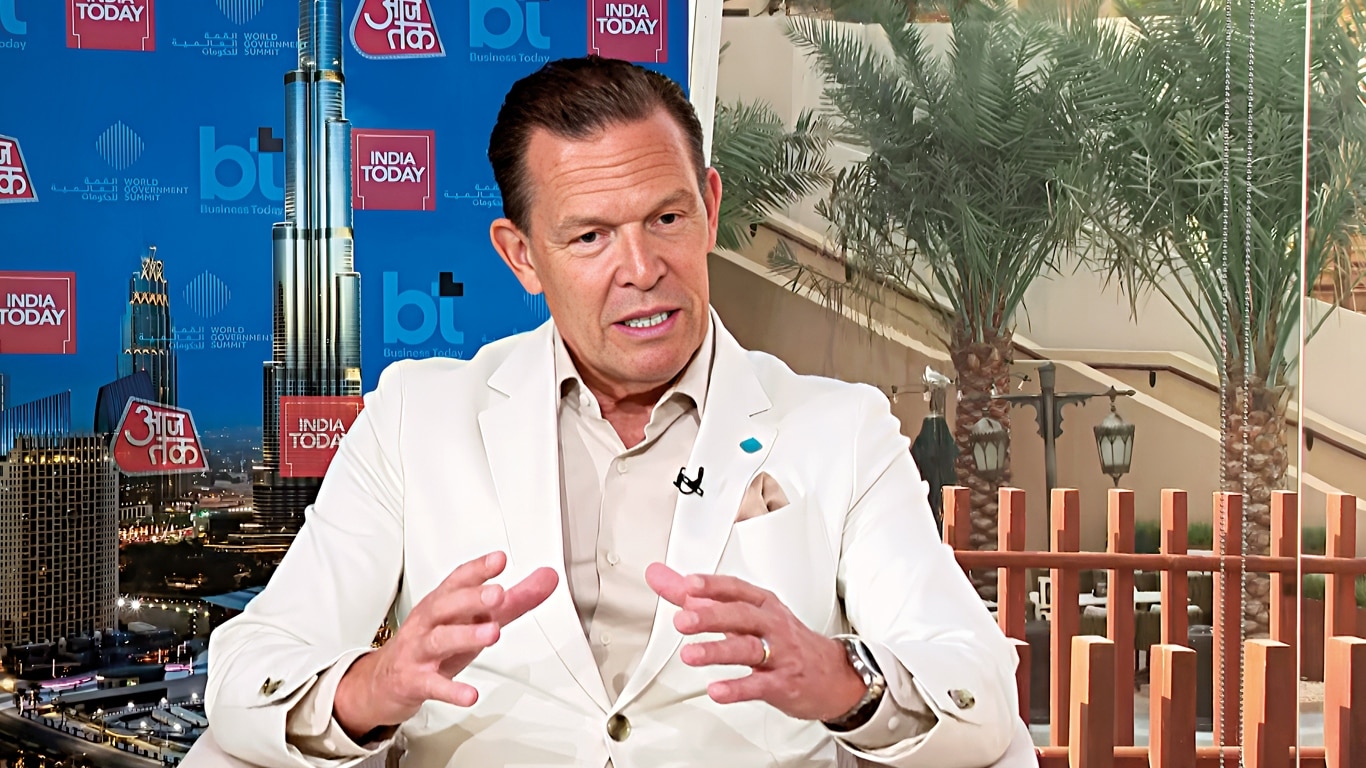

IBM CEO Arvind Krishna echoed this thinking, positioning technology as nothing less than a new pillar of national power.

“Technology is a force multiplier. Every nation is waking up to the fact that technology can help amplify the impact of both of those and many other industries,” Krishna said, referring to defence and finance. The shift, he added, means technology is becoming “as, or perhaps more important, even than finance” in driving future growth.

Krishna was careful to distinguish sovereignty from isolation. “It’s not exclusive. You can use many things from other places, but you do need to run some that you have your control over fully, so that nobody can turn it off, mismanage it, steal data from it, or apply the wrong security to it,” he said.

Who owns the intelligence?

That anxiety fuelled intense debate around “sovereign AI.” Alibaba Chairman Joseph Tsai and investor Chamath Palihapitiya both argued that the future belongs to open-source models.

“The future is open source,” Palihapitiya declared, “because it provides total transparency into what’s happening underneath the hood.”

Tsai explained that for governments concerned with data privacy, open source allows them to “claim sovereignty and claim ownership of the model” by deploying it on their own secure infrastructure.

Can trust survive automation?

The philosophical questions were equally pressing. In a packed roundtable featuring 31 media executives, the issue was not whether AI would transform journalism; it was whether journalism would survive the transformation intact.

India Today Group Vice Chairperson and Managing Director Kalli Purie offered a framework she called the “AI sandwich”: “You have human intent at the beginning, AI in the middle to help you augment, and then you have the human decision at the end.”

But she also raised a chilling generational question, “What if AI natives don’t see trust the same way as we do? What if a bit of lying and hallucination is okay by them? That raises very big existential questions for us on credibility.”

India Today Group Chairman Aroon Purie was unequivocal about where the line must be drawn.

“AI is just an engine. But the driver is a human, and also has the brakes,” he said. “In this world of abundant information, interpretation, meaning, and ethics is what humans have to bring to the table.”

From tools to intent

Elsewhere, the tension between automation and authenticity played out in consumer technology. Nothing CEO Carl Pei described a future where “everybody will have their own personalised operating system, because we’re all different.”

The shift, Pei suggested, is from asking machines to act to machines anticipating intent.