Rajiv Mittal, 53, does not have a grandson yet. But he is sure, if and when he does have one, the boy, on growing up, will continue in the business he has set up. Mittal is Chairman and Managing Director of the Rs 1,400-crore

water treatment firm VA Tech Wabag, and he knows rapid urbanisation, dwindling fresh water reserves, a widening demand-supply gap and a depleting groundwater table will keep the water treatment business thriving for a long time.

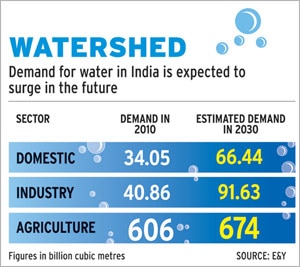

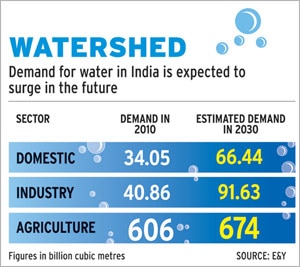

An Ernst & Young (E&Y) study says the Indian water sector could require investment of around $130 billion between 2011 and 2030. Wastewater management, in particular, is emerging as a key thrust area. Currently, only 60 per cent of industrial and 26 per cent of domestic wastewater is treated in India. Metros and large cities are treating only about 30 per cent while smaller cities treat a minuscule 3.7 per cent of their wastewater.

"It is not only industries. Even municipal corporations are being pulled up today if they do not meet environmental norms," says Mittal. Of his company's Rs 5,000 crore plus order book, municipal orders account for 60 per cent. When Mittal started business 15 years ago, he was more focused on the industrial segment but has gradually shifted emphasis to the municipal sector.

"You would expect us to earn more from industry but that is not the case," says Mittal. "Corporate houses negotiate very hard. Municipal orders are more rewarding and the size of projects is bigger." Such contracts can involve either domestic wastewater treatment or making water potable. For Mittal's company, the former comprises 65 per cent of municipal orders and the latter, the rest.

The

biggest consumer of water, however, is neither the domestic nor the industrial sector, but agriculture, taking up about eight times as much water as the other two put together (see Watershed). But domestic and industrial water requirements are increasing at a much more rapid pace than that of agriculture and are expected to double by 2030, while agriculture's will rise only 11 per cent. Overall, demand is expected to soon outstrip supply.

Rapid urbanisation has led to a surge in wastewater treatment and drinking water projects, says S.N. Subrahmanyan, whole time Director and Senior Executive Vice-President (Infrastructure and Construction), Larsen & Tourbo (L&T). All of them were initiated by municipalities and various urban water infrastructure boards. "This sector contributes close to 100 per cent of revenue in our wastewater segment. It also has a significant share in our water supply and distribution segment," he adds.

L&T recently bagged a Rs 1,017-crore project in rural Rajasthan to supply drinking water to 650 villages. But urban water management is more attractive for companies. "Maintaining status quo in the water sector is no longer an option for most of the developing countries. The beginning of the change is visible and there is good reason to believe that water will be an important investment theme for public, multilateral and private financial institutions in the coming decades," says E&Y in its report.

Wastewater treatment has been a largely neglected area because municipal bodies cannot charge water users for the service. They can, however, do so for potable water projects. So, while municipal bodies often do get funding for wastewater treatment projects, operating and maintaining treatment plants is still a challenge. If a municipality has to manage a sewage plant which cleans 60 million litres of water daily, the annual cost is around Rs 3.3 crore. Power is the single biggest cost.

Our plant can generate 2 MW of power from sewage and will not need a single unit from the grid: Rajiv Mittal, Chairman & Md, Va Tech Wabag

To streamline costs, companies like VA Tech Wabag have built captive power plants which utilise the sewage. Consider the recently inaugurated 45 million gallons per day Kondli Sewage Treatment Plant it built for the Delhi Jal Board. "Our plant can generate 2 MW of power from sewage and will not need a single unit from the grid. The only cost that remains is manpower, chemicals, etc," says Mittal. The green energy generated from such projects is also eligible for carbon credits. Business models like these can make projects viable.

Though the metros are waking up to the challenges of wastewater management, smaller cities still lag behind. "We have a long way to go. We have only now started talking about Tier II and III cities," says Mittal. According to industry estimates, Indians on average use 120 to 125 litres (33 gallons) of water daily, about half of this becomes wastewater. If harnessed, this can generate 940 MW power.

The Planning Commission, in its 12th Five Year Plan, for the period ending in 2017, has said that an investment of $26.5 billion is required to provide safe water to all Indians. The country will need consulting and engineering services support in water technology, including desalination and treatment of wastewater. Though the situation is better than before, funding for municipal projects is still a challenge. Therefore, companies prefer to take up projects initiated by the central government or funded by multilateral agencies. "A majority of the water-related projects are being executed for government bodies with JNNURM, Japan International Cooperation Agency, Asian Development Bank and World Bank funds. Hence revenue and cash flow have been reasonable," says Subrahmanyan of L&T. (JNNURM stands for Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission.)

Triveni Engineering, another company in the water sector, focuses on sewage treatment in municipalities and desalination projects. "We do half municipal and half industrial. The order book is skewed towards municipalities since these projects have longer gestation periods. We are bullish on this sector and are positioning ourselves as a niche technology player," says Executive Director Nikhil Sawhney. Last year, Triveni secured an order to set up a 100 million litres per day sewage treatment plant from the Haryana Urban Development Authority (HUDA). Triveni's water business has an order book of over Rs 600 crore.

Recycling and reuse of wastewater is gaining acceptance. It has also been encouraged by the Water Policy 2012. According to Mittal, industries in coming years will have to rely mostly on reuse of water and in some cases may even have to buy recycled water. Mittal's company has bagged a project in Tuticorin from the Tamil Nadu government to set up a sewage treatment and solid waste treatment plant. "We bagged the contract for just a crore. We will build the plant free, take ownership and operate. The treated water will be sold to industries and that will bring us revenue," says Mittal. This will be a first of its kind experiment in the country, he claims.

Currently, treated sewage water is being consumed primarily in industrial sectors but in future it may very well find acceptability as potable. "In Singapore, you get sewage recycled water everywhere. In Namibia, we have a 12-year old plant that treats sewage water and people consume it. The time is not far off when in India you will have no choice but to do it," says Mittal.