On the afternoon of June 18, a video featuring a group of men in Coimbatore shouting anti-China slogans and smashing smartphones went viral on social media. The same day, another group of men, this time in Surat, were seen doing the same to a TV set. This beat the earlier one in internet popularity due to its higher drama quotient.

The videos emerged less than 72 hours after the clash between Indian and Chinese forces at Galwan Valley in East Ladakh that led to the death of 20 Indian soldiers. Since then, relations between the two countries have been strained. This has manifested itself in a public campaign to boycott Chinese goods, especially smartphones and TVs, the two segments dominated by companies with Chinese origin. This swirl of nationalism has given fresh wind to local brands steamrolled into dust by the Chinese a few years ago. Companies such as Micromax, Karbonn and Lava in smartphones, and Onida, Weston, Salora, once household TV names, along with new entrants like VU Technologies, are sensing an opening to increase market penetration. Any real dent in demand, howsoever small, for Chinese products in the two categories, will throw up a sizeable opportunity for these local players.

Take smartphones. Around 158 million smartphones were sold in India in 2019. This made it the world's second-largest market behind China with revenues of $8 billion. Four of the top five bestselling brands in the country are Chinese, led by Xiaomi and Vivo and followed by Realme and Oppo. Together, they account for over 80 per cent of the market (Q1 2020). The domestic feature phone market is worth another 130 million units. The market leader is iTel, owned by Shenzhen-based Transsion Holdings. The hold of the dragon is relatively weaker in this segment.

In the nascent smart TV segment, which is in many ways seen as an extension of the smartphone market, China again accounts for the lion's share. Xiaomi is the market leader. It enjoys the company of compatriot TCL in the top five. Others are gearing up for action but more on that later.

In a highly competitive and technology-driven sector like consumer electronics, consumers rarely opt for newer or smaller brands. The anti-China sentiment, however, could provide a springboard for local brands to beat the heavyweights. But do they have the ability to exploit this opportunity or will it be business as usual once winter sets in and dust settles in the cold desert of Ladakh? Or will non-Indian, non-Chinese companies benefit?

Away from the border, a battlefield of another kind is being readied.

The Rise of the Chinese

The Chinese domination of India's mobile handset segment may seem overwhelming statistically but is very recent. In 2015, Chinese brands accounted for less than 20 per cent of the market. The majority pie was with local brands, as Micromax, Intex and Lava, among others, cornered nearly 40 per cent of the market.

Since then, the rise of Chinese brands has been as exponential as it has been relentless. By 2017, they had more than half the market. So much so that towards the fag end of the year, when Xiaomi upstaged Samsung to emerge as India's biggest smartphone maker, it did not feel like a flash in the pan. It has since then consolidated its position at the top.

The rise of the Chinese came at the cost of local brands. The local players were hamstrung by technology (most were sourcing it from China) and did not have pockets deep enough to withstand the onslaught. By 2018, their share had shrunk to 10 per cent. Today, less than 2 per cent buyers opt for local smartphone brands. "I cant think of any country where the Chinese have dominated like this," says Tarun Pathak, Associate Director, Counterpoint Research. "Everything fell in place perfectly for them from 2016 when they started accelerating. They were ahead of the curve and invested in 4G when local companies were still into 3G. Decline in data prices also helped companies like Xiaomi that had an online-first strategy. They also went for innovation in devices for India. Indian brands, on their part, were facing headwinds such as demonetisation and GST and were vulnerable as the Chinese built momentum."

Opening for Local

More than 75 per cent smartphone volumes come from phones that cost less than Rs 15,000. This is also the segment where Lava, Micromax, Karbonn and Intex operate. These brands are supported by government policies. For example, the product linked incentive scheme, launched by the Ministry of Electronics and Information and Technology in April this year, provides a 4-6 per cent incentive on incremental sales over FY20 levels. It favours local brands as, for international companies, a threshold value of Rs 15,000 has been stipulated, while there is no such condition for local firms. The investment criteria for local companies are also less stringent. Domestic firms need to invest just Rs 50 crore initially and Rs 200 crore incrementally over four years to avail the incentives, while for others, it is Rs 250 crore initially and Rs 1,000 crore over four years.

"Local players like us will get the benefit of various government schemes. It will enable us to build capacity to cater to export markets. This will facilitate building of a cost-efficient mobile manufacturing ecosystem with a huge potential to create employment opportunities," says Tejinder Singh, Head-Product, Lava International. "We plan R&D investment of Rs 800 crore over the next five years. We are already among the top five feature phone brands in the world. Our vision is to raise the Indian flag high in global skies."

While the anti-China sentiment is palpable, right from the man on the street to the bureaucrat in government offices, the most vocal voices against Chinese dependence have come from the trading community. Encouraged by policies such as Atma Nirbhar Bharat that aim for bringing down import dependence and catchy slogans like vocal for local, the Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT), the umbrella body of 40,000 trader organisations, is at the forefront of this campaign. CAIT has made a list of 500 products that it wants its seven crore member retailers to stop importing with an aim of reducing Chinese imports by $13.3 billion by December next year.

There is confusion, though, on classification of Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo, Realme, Poco and One Plus - companies with Chinese origin but manufacturing facilities in India. Like others, their phones are made locally, in factories run by Indians. Besides, their wide retail network provides livelihood to thousands of people across the country. "Anybody who is manufacturing in India should not be considered a foreign company," says Pankaj Mohindroo, Chairman, India Cellular and Electronics Association (ICEA). ICEA has joined hands with CAIT and is assisting the government in framing policies to bring down the import content in mobile phones. CAIT has written to celebrities like Aamir Khan, Virat Kohli, Ranbir Kapoor and Ranveer Singh, who endorse phones from these brands, to stop promoting these Chinese companies.

From toys and T-shirts to handicrafts, coffee mugs, watches and spectacles, Chinese goods are omnipresent in Indian markets, though a lot of them are classified as unorganised merchandise. But the ubiquitous mobile phone has earned the ire of the populace and become a symbol of Chinese domination. "Considering the impact of this movement, it will give impetus to Indian brands which have the capability to build products offering great experience and quality," says Singh of Lava International. "We are in the process of building a robust portfolio, which will have offerings for every segment."

Lava is the second-largest feature phone brand in India, and while its presence in the smartphone segment is negligible (around 1 per cent share), it is planning to launch a slew of smartphones in the next few months starting with Z61 Pro. It wants to replicate its success in feature phones in the smartphone market.

Similarly, Micromax, which has been testing its "Made in India-Made for India" smartphones, is planning to launch at least three products in the budget to mid-range segment that accounts for a bulk of the volumes. "We have seen a definite uptick in enquiries for our phones even though overall footfalls at stores are relatively low because of the pandemic. It has bolstered our confidence and we are planning to expand our portfolio and expedite our launches," says a Micromax executive. "Indian consumers now want to buy only Indian phones and nobody understands their needs better than us. We need to fulfil their aspirations."

A Matter of Scale

The success of local brands is not a given even with so much going in their favour. Experts say lack of scale is a big problem. Further, minimal presence at the present juncture means consumers do not have many choices apart from Chinese in some smartphone segments. "Chinese brands are facing a backlash from the consumer but it is very easy to misread the situation. These brands command more than 80 per cent (Q1 2020) of the market. So, where does he go even if he doesn't want to buy a Chinese phone?," asks Navkender Singh, Research Director, IDC. "In our mystery shopping exercise, we found that 7 out of 10 buyers ask for a non-Chinese phone but only three buy one, because of lack of options."

Another issue is fickle consumer sentiment. A business case built on that can be vulnerable. Pathak of Counterpoint says any real impact will be visible only if this sentiment against Chinese products sustains for another month and beyond. "In case of any event, the first four weeks are always about sentiment, when enquiries do not get converted into purchases. So, consumers are enquiring for non-Chinese phones at stores and realising there are not many options. So, they are not buying. If this sentiment prolongs for, say another month or so, we will start seeing some serious impact on the Chinese," says Pathak.

Past campaigns in favour of locally produced goods have fizzled out after the first few weeks without any fundamental change. Now, the impact is likely to be more permanent, but even then, lack of scale means Indian brands may not be able to fully exploit the opportunity. "Scale doesn't come overnight. Just because the situation is suddenly in your favour doesn't mean you can make two million phones overnight. That needs investments and commitment," says Singh of IDC. "If local brands start this journey and plant the seeds today and remain disciplined, then they can see the fruit of their efforts after two years. Otherwise, it will not mean much, as this sentiment will not last forever."

In the interim, the likes of Samsung, LG, Sony and Nokia may benefit more. These players, like the Indian companies, have lined up multiple launches in the run-up to the festive season starting September. For example, beginning next month, LG plans to launch six phones across price points.

Unlike the Chinese, who are getting flak for their roots, these companies have nothing to hide and are stressing transparency and data security to entice consumers. "Consumers will not simply look at the name of the brand they are purchasing but also the trust they have for it. With our European roots and proven track record, our phones are well-positioned in this aspect," says Sanmeet Kochhar, Vice President, HMD Global, which makes phones for Nokia.

However, the odds are stacked heavily in favour of Samsung, the only non-Chinese brand in India with big enough operations to cash in on any mistake by the major players. In terms of timing too, it is a god-send for the Korean firm, which just got over taken by Vivo as the second-largest smartphone maker in the country (Q1 2020). In feature phones, too, Lava has caught up with Samsung as the second-largest player. Samsung used to be clear market leader in both these segments in the not-too-distant past. "Samsung is the only mass-market non-Chinese brand with decent scale. So, it can benefit significantly," says Pathak of Counterpoint. "Anecdotal evidence suggests they have benefited a bit in the second quarter of this year. We foresee a close fight between Xiaomi, Samsung and Vivo in the third quarter. Samsung has a real chance of nudging ahead if it can play its cards right."

Virgin Territory in Smart TVs

Compared to mobile handsets, the smart TV segment in India is still evolving. In 2019, TV sales in India grew 15 per cent and topped 15 million units, with smart TVs estimated to have cornered a third of the market. It is a segment that is growing much faster than regular TVs at 25 per cent, mirroring the trend of smartphones outpacing feature phones.

Not surprisingly, the Chinese have made an early headstart in this category as well with Xiaomi having a 27 per cent market share. TCL is the only other Chinese player with a significant share (8 per cent). The only local brand of any significance is VU Technologies with a 7 per cent share. Others such as Onida, Salora and Weston are insignificant players. Just like in smartphones, the Chinese caught incumbents Samsung, LG and Sony napping in this segment too. "Brands like Xiaomi, TCL and VU have been expanding over the last few years taking on incumbents such as Samsung. LG, Sony and Panasonic. Furthermore, 2019 was marked by entry of smartphone brands such as Motorola, Nokia, OnePlus with their Smart TVs looking to build a connected device story," says Debashish Jana, Research Analyst for TVs at Counterpoint Research. "These new-age brands from Xiaomi to OnePlus offer high specifications and some unique features at highly affordable price points targeting urban users via e-commerce channels. This has led to some serious price cuts by competition to match the value proposition of these Chinese brands leveraging the cost-effective e-commerce channels."

The floodgates are just opening up. Realme threw its hat in the ring in the middle of the lockdown in May with its first smart TV while OnePlus expanded its range earlier this month with the more affordable U and Y series. Oppo is expected to join the fray in the next few months.

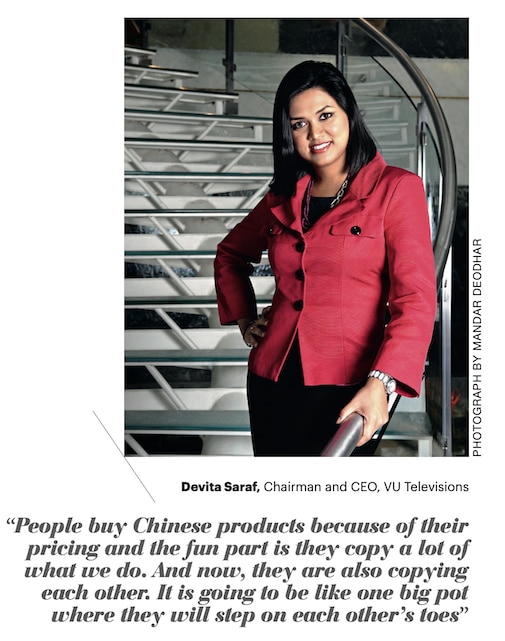

Devita Saraf of VU says the Chinese have similar strategies and will end up unleashing a price war and eating into each other's share, leaving the rest of the market for others. The current negative sentiment also works against them. "People buy Chinese products because of their pricing and the fun part is they copy a lot of what we do. And now, they are also copying each other. It is going to be like one big pot where they will step on each other's toes. It's not my job to jump into that battle," she says. "Of course, the anti-China sentiment is helping us, as at this point people don't want to buy Chinese brands and are seeing value in a brand like us, even though we are more expensive. (But) We are competing with the likes of Sony, Samsung and LG from day one and successfully taking market share. In any case, nobody is going to buy a very high-end product from them."

The lower end of the market is where the likes of Onida and Weston come in. But lack of scale could be a hindrance for them as well. "A smartphone has become a use and throw product but not a TV. Also, it is a bulky product, so manufacturing it on a large scale is capital intensive. I doubt if the fringe players will be able to suddenly light a bulb and beat the Chinese at their own game," says an industry insider.

A chunk of India's consumer electronics market is up for grabs but the consumer isn't really spoilt for choices right now.

@sumantbanerji