September 5, 2008

Oddanchatram (Tamil Nadu)

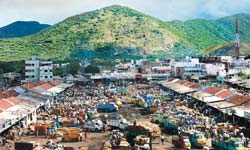

Incessant overnight rains have left the ground slushy at the Oddanchatram Gandhi Vegetable Market, located on the picturesque foothills of the Western Ghats, some 93 km from Madurai in southern Tamil Nadu.

We are in the Oddanchatram market to study the impact of retail chains on traditional markets. Why Oddanchatram? This 33-year-old vegetable market is the largest in Tamil Nadu in terms of direct procurement from farmers (and one of the biggest in south India), with average daily volumes of over 1,000 tonne of vegetables. A wide variety of vegetables are cultivated on 3,000 hectares in a 20 km radius of the town. Also, major retail chains such as Reliance Retail, Aditya Birla Retail and Spencer’s Retail have set up procurement centres here to feed their outlets across south India. And, if local traders are to be believed, Wal-Mart and Subhiksha will also come calling soon. In fact, Aditya Birla Retail’s procurement centre here, set up in February this year and housed a few kilometres away from the market, is its biggest in south India.

We bump into A. Kalimuthu, a farmer with 10 acres of land in Keeranur village, 15 km away. He is reasonably happy, having just sold seven sacks of small onions (70 kg each) at Rs 14 per kg. We ask him whether he would have got a better price selling to the retail chains. “Though they pay slightly more, they buy only the best quality produce.

Kalimuthu has always sold his produce in the market. There are several buyers here and that ensures that whatever quantity he brings is sold. “I cannot afford to take the stock back home as it is perishable.

More importantly, produce of varying qualities is accepted in the market— though better quality vegetables fetch higher prices,” he adds. A quick (and, admittedly, unscientific) survey across the market reveals that most farmers avoid the retail chains for the same reasons.

What threat?

|

The story at Spencer’s Retail is similar. There is some action at the Birla centre, which, surprisingly, does not have a name board. Hybrid tomatoes brought in by farmers are being graded according to the required specifications—diameter of 45mm to 70 mm, not more than 12 to 15 per kg, glossy appearance, not over-ripe and 50-60 per cent red in colour.

“To cater to our customers’ needs, we procure only the best quality vegetables. At the same time, we work closely with farmers to help them get that quality. We run a Farmers’ Productivity Improvement Programme, specify the right hybrids, help them with their choice of seeds and educate them on best agricultural practices through training programmes,” says K. Parameswaran, Cluster Manager-Sourcing (Tamil Nadu & Kerala), Aditya Birla Retail. In August, this centre procured 257 tonne compared to 173 tonne in June. It plans to open many more such centres in south Tamil Nadu and double its procurement by the end of this year, adds Parameswaran. But at 20 to 30 tonne a day, procurement by the the retail chains pales into insignificance compared to the average daily trade (of 1,000 tonne) in Oddanchatram.

It is 2.00 p.m. by the time we return to the market, and the level of activity has increased manifold. Tomatoes, beans, cauliflowers, drum sticks and coconuts are being unloaded.

By evening, the frenzy has hit an even higher pitch. It is difficult to walk through the market without the fear of being run over by trucks or hit by men carting huge sacks of vegetables. A coconut auction is on. Coconuts of different sizes and from various farms are neatly piled up and coded. An agent is auctioning the nuts. Within 15 minutes, over 5,000 nuts are sold.

The sun has begun to set. As we drive eastward and leave Oddanchatram town behind, the spectre of retail chains swamping the traditional markets appears bizarre—for now, at least.