China’s more direct approach focuses on engineering reliability over scientific flexibility.

China’s more direct approach focuses on engineering reliability over scientific flexibility.

China’s more direct approach focuses on engineering reliability over scientific flexibility.

China’s more direct approach focuses on engineering reliability over scientific flexibility.China is racing to outpace the West in one of space science’s biggest prizes: bringing Mars samples back to Earth. Its Tianwen-3 mission, launching in 2028 and returning by 2031, could beat NASA and the European Space Agency’s delayed Mars Sample Return — and seize a geopolitical and scientific coup.

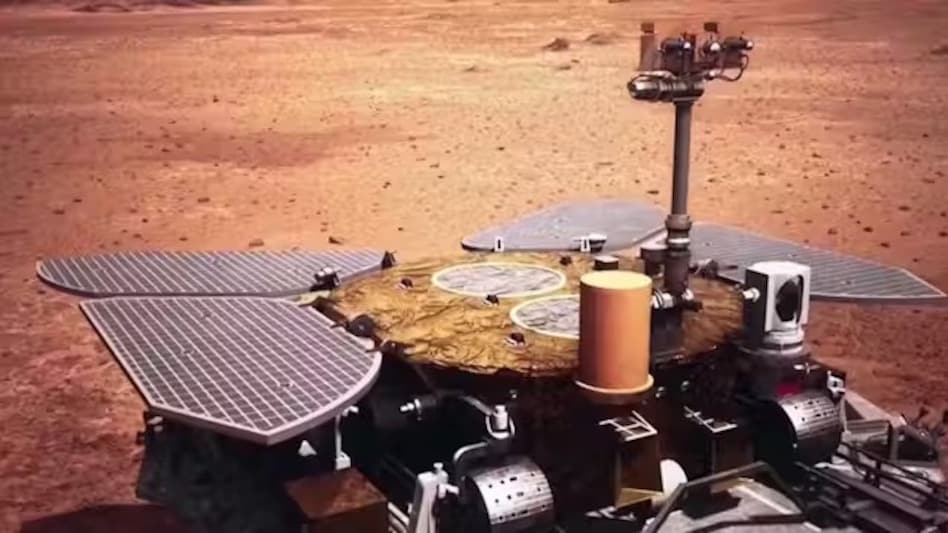

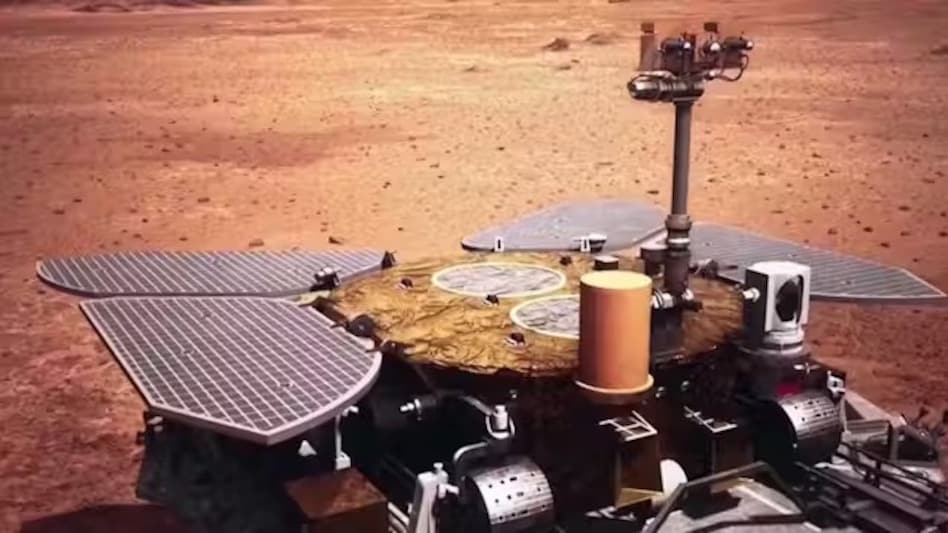

China’s ambitions have surged since May 2021, when its Tianwen-1 mission made it the second nation after the US to land on Mars. The Zhurong rover explored Utopia Planitia, paving the way for bigger goals.

Tianwen-3 is the next step. Two rockets will launch from Hainan Island: one carrying a lander, the other an orbiter and Earth-return vehicle. The plan is to collect at least 500 grams of Martian soil and rock, which will be launched into Mars orbit and captured for return to Earth.

Landing is expected in Mars’s mid-northern latitudes, at lower elevations to aid descent. The mission leverages China’s Chang’e lunar technology. The lander will drill up to two meters underground and scoop surface material.

A standout feature is a helicopter drone, modeled on NASA’s Ingenuity, able to collect samples within 100 meters of the lander. For about two months, the lander will also deploy tools like a Raman spectrometer and ground-penetrating radar to analyze the site’s geology.

After collecting samples, a solid rocket booster will loft the container into orbit for rendezvous with the orbiter. Once back on Earth, the materials will go to a lab built under strict protocols to avoid contamination.

At the heart of Tianwen-3 is the hunt for signs of life. Researchers aim to detect biosignatures — chemical or structural traces of past or present organisms. Li Yiliang, an astrobiology professor at the University of Hong Kong, notes these might include “molecules used by living organisms, biogenic isotope fractionation, and fossil imprints in Martian rocks.”

While NASA’s Perseverance rover has spent years collecting carefully chosen samples from Jezero Crater, China’s more direct approach focuses on engineering reliability over scientific flexibility. “This is exactly what we have been recommending over the years,” said Mahesh Anand, planetary science professor at the Open University in England.

Casey Dreier of the Planetary Society calls China’s method “symbol-driven and capability-focused over the direct science return.” Yet with Tianwen-3, China may be first to bring Mars to Earth — and redefine humanity’s search for life beyond our world.