The ruling should prompt India to re-examine its trade deal with the United States. Here's why

The ruling should prompt India to re-examine its trade deal with the United States. Here's why The ruling should prompt India to re-examine its trade deal with the United States. Here's why

The ruling should prompt India to re-examine its trade deal with the United States. Here's why1-US Supreme Court Ruling

The February 20, 2026, decision of the Supreme Court of the United States has abruptly reshaped the global trade landscape. By ruling that President Donald Trump lacked authority to impose sweeping “reciprocal tariffs” under the IEEPA, the Court closed the fastest route for economy-wide tariffs and reasserted Congress’s control over trade policy. Within hours, the administration announced a temporary 10% global tariff under Section 122, highlighting both Washington’s determination to preserve trade leverage and the growing legal uncertainty surrounding U.S. tariff policy.

2-New 10% global tariffs as a response to the court ruling

Following the Supreme Court ruling, the Trump administration issued an order on Feb 20 imposing a 10% import duty on most goods entering the United States. This will be valid for 150 days, effective February 24, 2026. This across-the-board tariff relies on Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974.

But the use of section 122 is also on a weak legal footing and likely to be challenged, as explained later in this note.

3-Impact

The Supreme Court’s ruling strikes down the country-specific “reciprocal tariffs” and fentanyl-linked duties imposed on imports from major US trading partners. More broadly, it reasserts Congress’s authority over trade policy and sharply limits a president’s ability to use emergency powers to impose sweeping tariffs.

The decision also weakens the rationale behind several recent US trade deals with partners such as the UK, Japan, the EU, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and India, which were negotiated to avoid higher tariffs.

With a temporary 10% tariff now in place — and even that facing legal uncertainty — partner countries may question the value of those agreements, some may dump them as being useless and one-sided.

Still, some may hesitate to abandon them, given concerns about provoking the Trump administration, the temporary nature of the 10% duty, and the risk of future tariffs or sanctions if relations deteriorate.

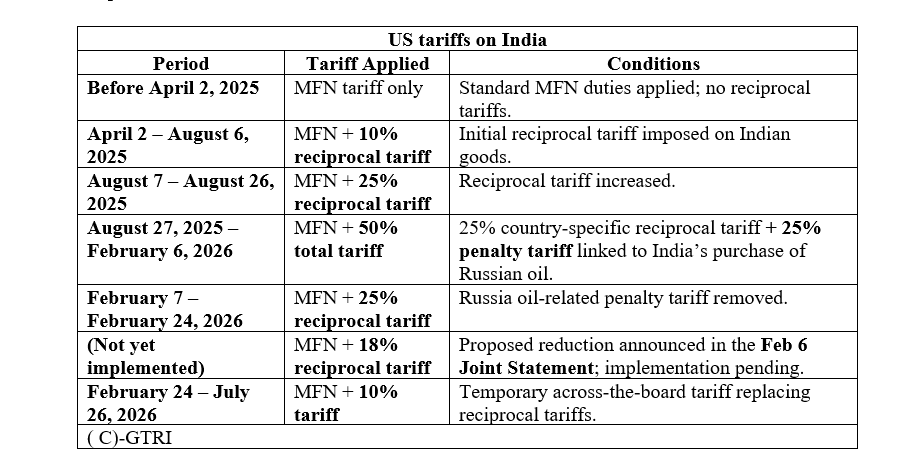

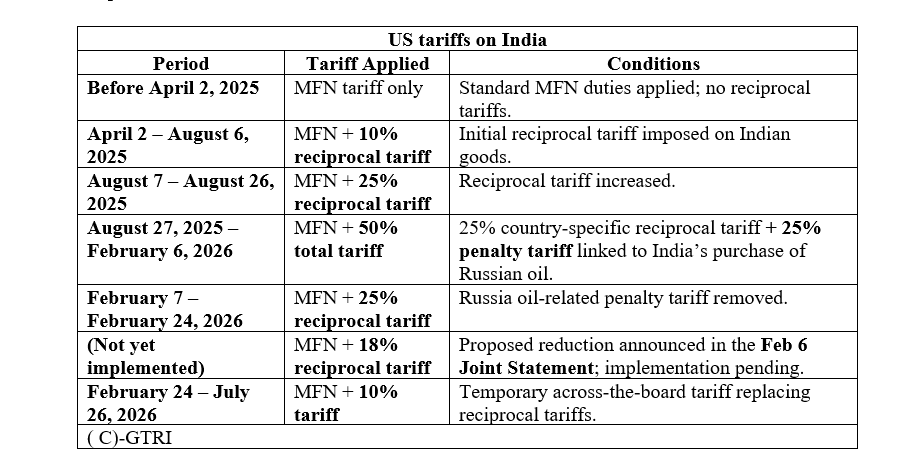

4-Changing US tariffs on India

Before April 2, 2025, the United States applied only standard MFN tariffs on Indian goods. From April 2 to August 6, 2025, it imposed an additional 10% reciprocal tariff. This was raised to 25% from August 7 to August 26, 2025. Between August 27, 2025 and February 6, 2026, total additional duties rose to 50%, consisting of a 25% country-specific reciprocal tariff plus a 25% penalty linked to India’s purchases of Russian oil, over and above MFN rates.

From February 7 to February 24, 2026, the Russia-oil penalty was removed, reducing the additional duty to 25%. The February 6 joint statement proposed lowering this reciprocal tariff to 18%, but the change has not yet been implemented. Beginning February 24, 2026, a temporary across-the-board 10% tariff will apply for 150 days in addition to MFN duties, replacing the earlier reciprocal tariff structure.

5-Options for India

Removal of the reciprocal tariffs will free about 55% of India’s exports to the United States from the 25% duty (including the 18% rate yet to be implemented under the interim framework announced in the February 6 joint statement), leaving these exports subject only to standard MFN tariffs.

On the remaining exports, (i) Section 232 tariffs will continue — 50% on steel and aluminium and 25% on certain auto components — while (ii) products accounting for roughly 40% of export value, including smartphones, petroleum products and medicines, will remain exempt from U.S. tariffs.

The ruling should prompt India to re-examine its trade deal with the United States.

After offering concessions — including reducing MFN tariffs, aligning economic policies with U.S. interests, easing regulations affecting U.S. goods, and signalling large purchases of U.S. products — India was to receive an 18% reciprocal tariff rate. Now, even without a trade deal, India, like other countries, faces a 10% tariff on most goods, rendering the agreement being negotiated useless.

The US-India Joint Statement dated Feb 6, 2026, mentions, “In the event of any changes to the agreed upon tariffs of either country, the United States and India agree that the other country may modify its commitments”. Now that US tariffs have changed, India should use this clause to either opt out of the trade deal or delay negotiations or seek fresh terms so the trade deal looks equitable.

6-Options before the Trump Administration to impose tariffs on new grounds

Even after the court blocked the emergency-powers route, a U.S. president still has a few legal pathways to impose tariffs — though each is limited and harder to use.

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 allows a president to impose temporary tariffs to address serious balance-of-payments deficits. It has never been used in the 50 years since it was enacted, and any tariffs imposed under it expire after 150 days unless Congress extends them. The provision was designed for the era of fixed exchange rates, when countries faced currency crises and external payment shortages.

Since the world moved away from that system in the 1970s, the law applies only in the event of a major international payments crisis — a condition the United States does not face today — placing the proposed 10% tariff announced on February 20, 2026, on an uncertain legal footing.

Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930 permits retaliatory tariffs if foreign countries discriminate against U.S. exports, but it requires strong proof and has never been used in modern practice.

More familiar tools remain available but are narrower and slower.

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows import restrictions on national security grounds (recently used for steel and aluminium), while Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 targets unfair trade practices but requires lengthy investigations before tariffs can be imposed.

Bottom line: sweeping tariffs are harder to impose now. Legal options exist, but they are slower, more limited, and vulnerable to legal challenge.

7-Reference-Tariff History

The dispute traces back to April 2, 2025, when President Trump declared America’s chronic trade deficit a “national emergency” and imposed 10% tariffs on nearly all imports, later raised to as high as 50% on selected countries. The U.S. administration argued that decades of trade deficits had weakened the U.S. industrial base and posed an economic threat. Critics, however, called the justification unprecedented, noting that the U.S. has run trade deficits since 1975 without such action.

The IEEPA was originally crafted to let presidents restrict financial or property transactions with hostile foreign powers—not to impose general tariffs. Still, the administration relied on it to impose tariffs and collect an estimated $100 billion in new customs revenue.

Three lower courts have already ruled against the Trump administration:

The Supreme Court on August 23, 2025, agreed to take up the administration’s appeal, amid warnings from both sides about the economic stakes. The justices will consider two core issues: jurisdiction and presidential power.

8-Finally

Taken together, the ruling and the temporary tariff response inject significant uncertainty into global trade relations and ongoing negotiations. Countries that made concessions to avoid higher U.S. tariffs may now reassess the value of those agreements, while the legal fragility and short duration of the 10% tariff complicate business planning and diplomatic strategy. For India, the decision narrows the expected benefits of its pending trade arrangement and underscores the need to recalibrate negotiating positions. More broadly, the episode signals that future U.S. tariff actions will face tighter legal scrutiny, making US trade policy less predictable but more anchored in congressional oversight.