Art had become an exclusive domain of a very few, says SAF founder Sunil Kant Munjal

Art had become an exclusive domain of a very few, says SAF founder Sunil Kant Munjal

Art had become an exclusive domain of a very few, says SAF founder Sunil Kant Munjal

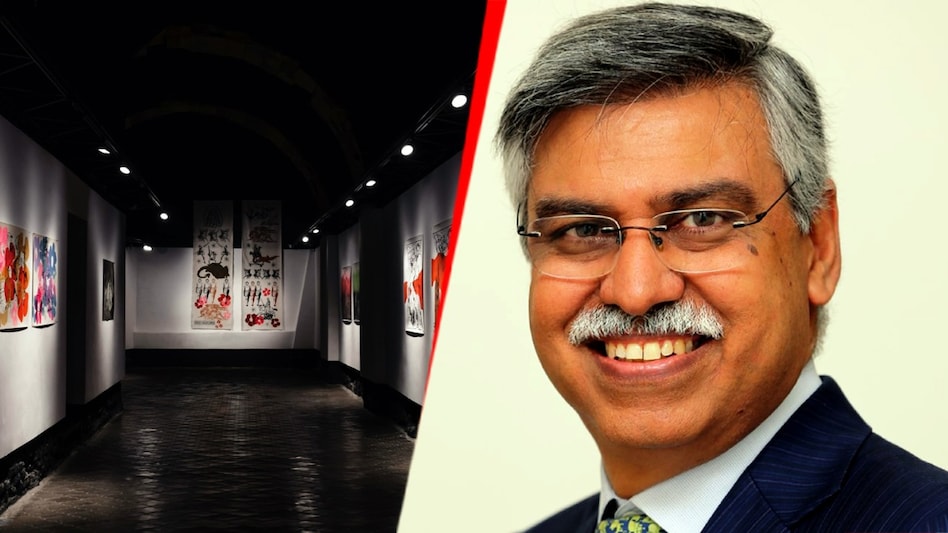

Art had become an exclusive domain of a very few, says SAF founder Sunil Kant MunjalA decade ago, Sunil Kant Munjal, Chairman of Hero Enterprise, envisioned a large multi-disciplinary arts festival that would showcase the vast talent that India has and make art accessible to all. This year, celebrating its 10th milestone edition, the Serendipity Arts Festival (SAF) that is taking place in Panjim, Goa, from December 12 to 21, has over 250 projects curated by more than 35 leading voices, bringing together artists, performers, musicians, chefs, designers, and storytellers from across India and the world. Over the years, SAF has created a permanent spot in the cultural calendars of visitors from over 60 countries, recording footfalls of over a 100,000 people daily. In a freewheeling conversation, Munjal, Founder & Patron, Serendipity Arts Foundation, talks about the inspiration behind the festival, the need for private sector to shoulder cultural responsibility in India, their new initiative to fund start-ups working in art and culture and a lot more. Edited excerpts:

Q: What was the inspiration behind setting up a large multi-disciplinary art festival such as Serendipity Arts Festival?

The reality is that art has always been around. But I think a few things were missing. One, there was no conversation between the artforms themselves. Not just the coexistence, but actually conversing and working together was missing. And the second was that the access to the arts had become highly limited. Art had become an exclusive domain of a very few. That sadly had become the norm the world over. And also, for us in India. And the third thing I found was that for an artist, it was very hard, unless you were the top known branded artist in the country to get any exposure to the actual public. So, the idea was to make art accessible, more multi-disciplinary, give newer artists exposure to the public and of course, have fun!

Q. To what extent have you achieved your goals in the last decade and how has the festival evolved?

I think we have achieved to a significant extent our aim to make art more accessible. We have some of the most renowned artists come in. We also have completely unknown artists coming in. We have artisans sitting there and performing. The festival has grown organically almost every year.

We have also done a lot of work in terms of interdisciplinarity of the arts. Almost 50 per cent of the festival is commissioned by us and we insist a large number of those projects must be multidisciplinary.

Also, over the years, the festival has evolved from being just a few days in Goa, to having activities through the year. We run residencies, research projects and publications during the year.

We are a large publisher now of research on arts and culture. And we've started taking the festival around as well to different places. This year we took it to 10 cities including Birmingham, Varanasi, Ahmedabad, Chennai, Delhi, Dubai and Paris. Right now, it’s a little trailer where we do 1-2 days in other cities.

Q: Should cultural festivals become like a formal part of our tourism calendar?

For sure, they should be an active part of our social lives. But I think even more than the festivals is the ongoing access and availability to art and culture institutions such as museums, theatres, galleries, etc. We have such an amazing depth and breadth of talent.

And you can see this in the arts around us, but the access is highly limited. When you design a city, part of the infrastructure, must be cultural. Otherwise, it’s not a sensible city at all.

We have launched the smart city programme for nearly a 100 cities but I don’t know how many are actually building new cultural institutions. You go to a small place in Spain or in Italy, you go to Mexico City. There are 200 private museums. Forget the public ones, by the way.

We frankly have a richer cultural heritage than most countries put together.

Q So do you think private philanthropy needs to shoulder cultural investment in India?

Absolutely. I think both need to supplement each other. I don’t think one can replace the other, by the way. No, of course not. The government has a real role. Please remember right through history, big patronage started from the palaces first. That’s a global phenomenon. Later the temples and the churches took over. And then the big role was played by governments. Governments created a lot of the infrastructure, the policy framework, the funding support, etc. I think the government became the big patron during occupied India.

And that continued post-independence.

I think the role of the private enterprise and private individuals, philanthropists, foundations, needs to be a lot more in this area than it is so far. A large part of the private support is going to areas like education and healthcare or religious places. But sadly, culture has not been high on our list of priorities.

I think that needs to change because we do not often think enough about the positive impact it can have on society, on culture, on behaviour, and even decision making. The best leaders in the world are those who not only were very good at technology or science, but who also read, who were interested in poetry, who liked art. So, it is important for the left brain and right brain, both to be in play for the best decision making to take place.

Which is why I think the private sector has a really critical role to supplement whatever effort the government makes. We have to step in as well.

Q. Could you tell us a little about your new initiative The BRIJ?

We hope to have it up and running in the next few years. It'll be a unique place of multiple cultural institutions at one place. The campus is going to be in Delhi.

It’s being designed and built as a global institution where multiple art forms will interact with each other. One of its key features is an incubator that we have already launched. We as a business are quite deeply involved in the start-up ecosystem. But for most start-ups and incubators in India the focus has been on FinTech, HealthTech or EdTech and areas such as these. So, the question we were asking ourselves was what about art? What about culture that's foundational and civilizational to all of us? Why should that not benefit from this miracle of technology that is taking place around us? So, we started an incubator a few months ago where the majority of the projects that get incubated will have to be start-ups based on arts and culture.

And we’ve already looked at well over a hundred projects and have funded a few. It is wonderful to find a lot more than we had expected. In fact, when we first suggested it, people said it may not work as we are unlikely to find enough people wanting to have a start-up in art and culture. But we are getting proposals from all over the country and it is very encouraging.

Q. You are also launching a book, A Table For Four. What is that about?

So, this is not my book alone. There are three of us who are writing it -- Nitan Kapoor, Ajay Shriram, and me. But the book is about four of us, three of us, plus Deepak Nirula (of Delhi’s favourite Nirula’s), who sadly we lost. We have been going out for lunch every six weeks or so for the past 17 years now.

And at each of these restaurants, in each of these lunches, we would also write a review. We would review the dishes, we would review the service, even go as far as look at the loo in the restaurant and see what its like. We were just doing it for ourselves. There was never any thought for a book. But when we got to a certain number of 50 or 60 restaurants, then this conversation came up that this might make interesting reading for people. And so earlier this year we finally put this to a test to ourselves and we started putting this together.

But then we went beyond just our own reviews. We went and spoke with some of the top chefs in and around Delhi as to their motivations, why they do what they do. We also looked at the history and legacy of restaurants in Delhi. So, it's really become a unique anthology now. It's called A Table for Four. Because that's how we used to order.