According to TaxBuddy, buyback activity across India has slowed dramatically since October 1, 2024, when the government shifted the tax burden from companies to shareholders.

According to TaxBuddy, buyback activity across India has slowed dramatically since October 1, 2024, when the government shifted the tax burden from companies to shareholders.

According to TaxBuddy, buyback activity across India has slowed dramatically since October 1, 2024, when the government shifted the tax burden from companies to shareholders.

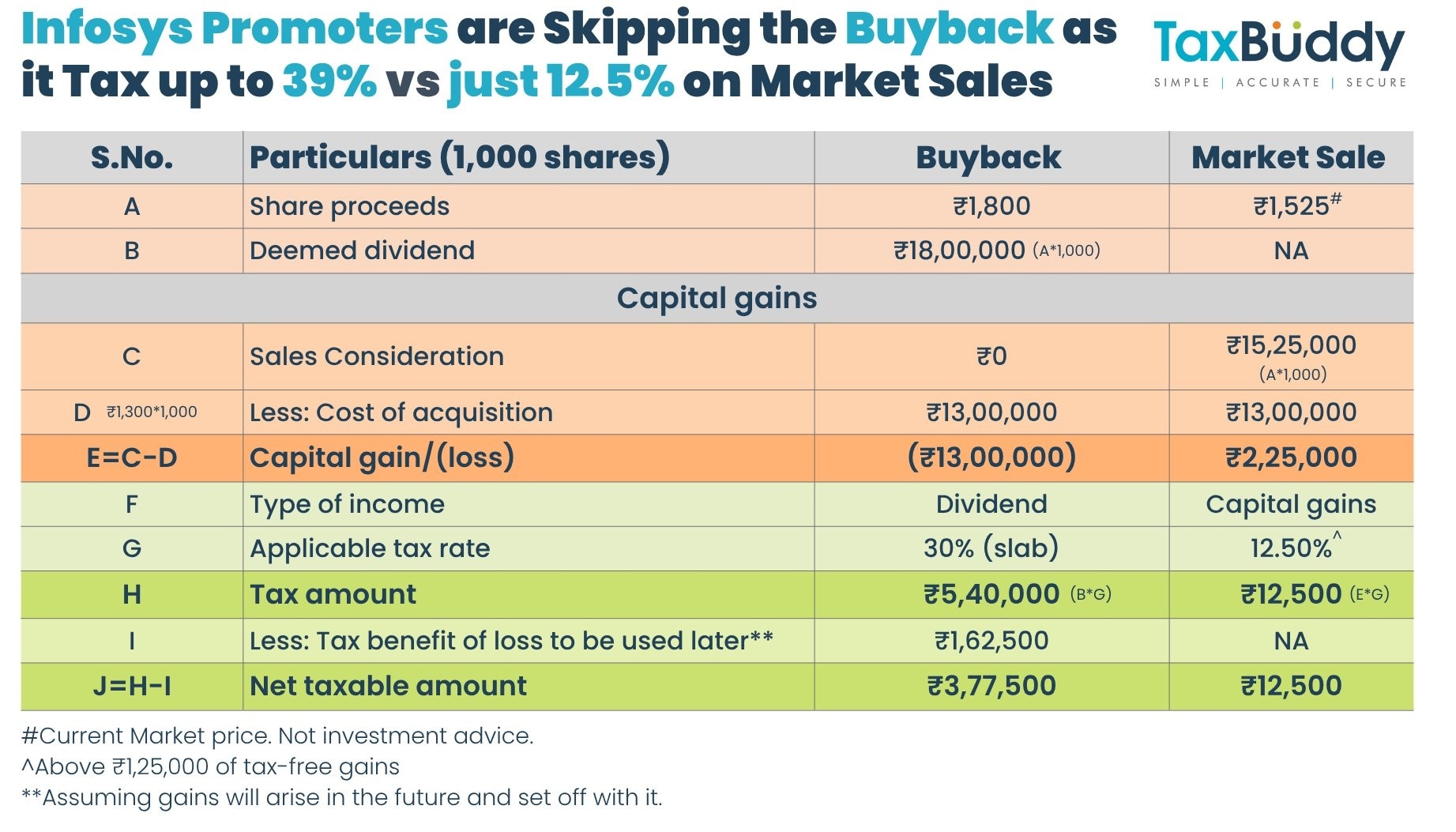

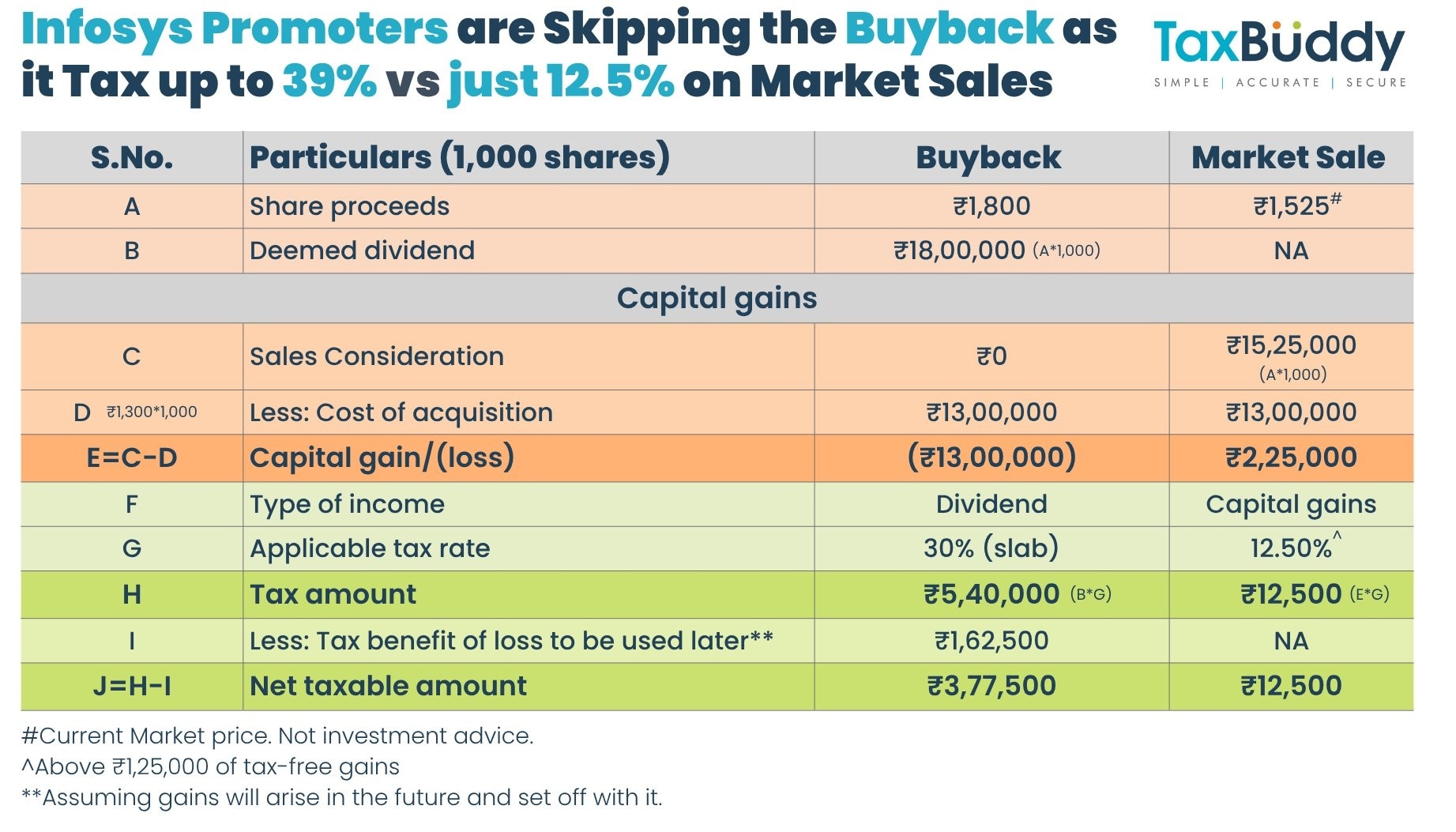

According to TaxBuddy, buyback activity across India has slowed dramatically since October 1, 2024, when the government shifted the tax burden from companies to shareholders.As Infosys’ Rs 18,000 crore buyback draws headlines for its record size and for promoter non-participation, tax advisory platform TaxBuddy.com has ignited debate over what it calls India’s “inefficient buyback tax regime”. The firm’s detailed analysis on social media this week breaks down how recent amendments to the Income Tax Act have fundamentally altered the math behind buybacks — and why corporate and promoter participation is now declining.

New Rule

According to TaxBuddy, buyback activity across India has slowed dramatically since October 1, 2024, when the government shifted the tax burden from companies to shareholders. Earlier, companies paid a 20% buyback distribution tax, shielding investors from any direct levy. Now, however, the entire buyback receipt is taxed as dividend income in the hands of the shareholder — and this, TaxBuddy argues, has upended the incentive structure.

It explained the situation using a simple example:

Infosys case:

Number of shares: 1,000

Cost per share: Rs 1,300

Buyback price: Rs 1,800

Gross receipt: Rs 18,00,000

Under the old system, the investor would have paid capital gains tax only on the profit — Rs 5,00,000 (Rs 1,800 – Rs 1,300 × 1,000). Now, the entire Rs 18,00,000 is taxed as income.

How the new buyback tax works

From October 2024 onwards:

The entire buyback receipt is treated as dividend income under the head “Income from Other Sources.”

The applicable tax rate is the investor’s income tax slab.

For top-bracket individuals, this could mean a 30% rate plus cess, taking the total liability close to ₹5.4 lakh on Rs 18 lakh of proceeds.

"This means you are paying slab-tax now and carrying a capital loss later,” TaxBuddy explained, adding that the earlier benefit of capital gains taxation is gone.

Capital loss with limited relief

Here’s where the distortion deepens. Because the buyback is treated as dividend income, the sale consideration for capital gains is deemed NIL, creating an artificial capital loss equivalent to the investor’s cost of purchase — in this case, Rs 13,00,000.

TaxBuddy clarified that this Long-Term Capital Loss (LTCL) can only be set off against future long-term capital gains (LTCG) and cannot be adjusted against the dividend income taxed in the current year. The unutilised loss can be carried forward for up to eight years, but that provides only deferred relief, not an immediate tax benefit.

In short, investors face a double hit — paying full income tax upfront while having to wait years to offset the resulting capital loss.

Why buybacks have lost their shine

TaxBuddy concluded that this tax structure has made buybacks far less appealing to high-net-worth individuals and promoters. “The earlier framework ensured tax symmetry — the company paid, investors received. Now, both compliance complexity and tax outflow have increased,” the firm noted.

The advisory added that corporate buyback activity has visibly declined, as the new system “penalizes” those who tender shares. For smaller investors, the impact varies by slab, ranging from 5–20%, but for ultra-rich shareholders, the effective rate can touch 40% — wiping out much of the gain from price premiums.

The larger picture

The October 2024 amendment was intended to end the tax arbitrage between dividends and buybacks, but experts now argue it may have swung too far. Promoters of large-cap firms such as Infosys, who previously participated in buybacks as a form of capital return, are now opting out entirely due to the high marginal tax hit.

Ved Jain, former ICAI president, explained on LinkedIn that recent tax amendments have reduced the appeal of Infosys’ buyback for resident investors. While the company is offering Rs 1,800 per share against a market price of around Rs 1,472, the tax burden outweighs the gain. Jain noted that after the Finance (No. 2) Act, 2024, amounts received from a buyback are treated entirely as dividend income. For high-income individuals, taxed at an effective rate of 35.88 percent, this means a tax of roughly ₹646 on the Rs 1,800 payout, leaving only about Rs 1,154 in hand. He said this is the key reason promoters are not participating.

With the new regime in place, TaxBuddy predicts India could see a continued decline in large buyback announcements, as companies reassess how best to reward shareholders. “Unless the tax framework is rebalanced,” it said, “buybacks may no longer be the preferred tool for capital distribution in Indian markets.”