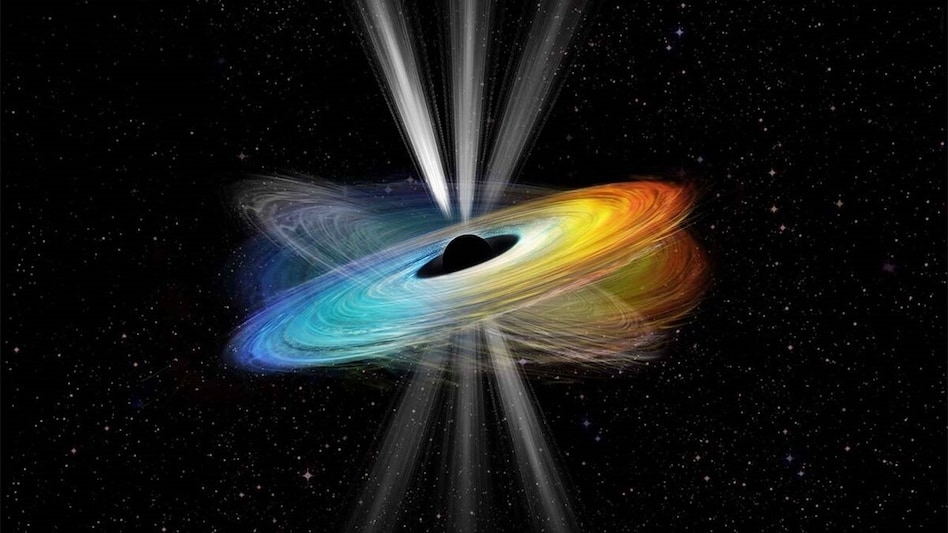

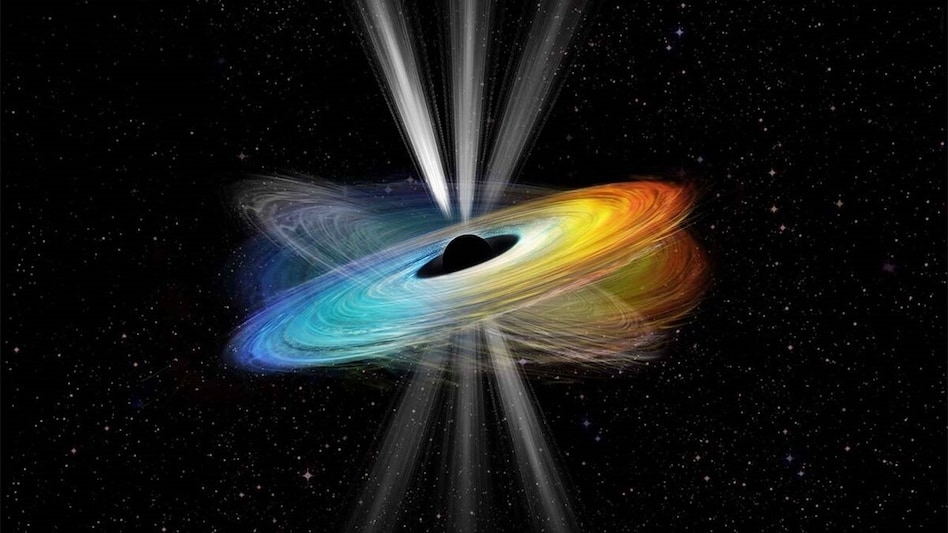

By drawing energy from rotation just as theory predicted near black holes scientists have recreated a cosmic phenomenon once thought impossible outside deep space.

By drawing energy from rotation just as theory predicted near black holes scientists have recreated a cosmic phenomenon once thought impossible outside deep space.

By drawing energy from rotation just as theory predicted near black holes scientists have recreated a cosmic phenomenon once thought impossible outside deep space.

By drawing energy from rotation just as theory predicted near black holes scientists have recreated a cosmic phenomenon once thought impossible outside deep space.For decades, physicists imagined harnessing the exotic physics of black holes right here on Earth. Now, a spinning aluminium cylinder in a quiet UK lab has brought that fantasy closer to reality. By drawing energy from rotation just as theory predicted near black holes scientists have recreated a cosmic phenomenon once thought impossible outside deep space.

In 1971, physicist Yakov Zel’dovich proposed an audacious idea: black hole-like energy extraction might not need a black hole at all. He imagined waves bouncing off a rapidly spinning object, emerging stronger each time by stealing rotational energy — a process that could escalate into a feedback loop. He called for mirrors to keep waves circling the cylinder, amplifying them with each pass. The theoretical setup became known as a "black hole bomb." Until now, it was just theory.

At the University of Southampton, that idea has finally come alive. Led by Hendrik Ulbricht and Marion Cromb, researchers built an experiment around a spinning aluminium cylinder. They wrapped it in a rotating magnetic field and a resonant circuit acting like a mirror, reflecting waves back toward the cylinder.

From what began as background noise, powerful signals emerged. With every pass, the electromagnetic waves gained strength — not from an external source, but from the cylinder’s spin.

“We’re generating a signal from noise — just like in the black hole bomb idea,” Ulbricht said. The experiment echoed Roger Penrose’s 1969 concept of energy extraction from rotating black holes, now recreated on a lab bench.

The mechanism at play is known as the Zel’dovich effect. When a spinning object moves faster than the waves approaching it, the waves can shift into negative frequencies — a rotational version of the Doppler effect. This lets them draw energy from the object itself.

The team had previously tested the theory using sound waves and a spinning disc. This time, using electromagnetic waves proved far more complex. But they spun the cylinder fast enough to achieve negative absorption — meaning amplification.

“You send in a wave and get more back — amazing,” said physicist Vitor Cardoso from the University of Lisbon. It was the first real lab demonstration of such a cosmic effect.

The team even observed instability, where wave amplification spiraled out of control, draining the cylinder’s energy and eventually fizzling out — mirroring behavior seen near black holes.

Beyond proving the theory, this result has broader implications. Superradiance — the process of extracting energy from spin — could offer a new tool for studying dark matter. Some theories suggest that if unknown particles exist, they might cluster near spinning black holes and sap their energy, leaving detectable traces in gravitational waves. Cardoso suggested that black holes might work better than particle colliders for detecting these elusive entities.

The Southampton team reported how the cylinder acted like a self-sustaining engine. Once triggered, wave amplification grew until the spin slowed below a critical point. The next step? Testing whether quantum vacuum fluctuations could kickstart the wave growth. That challenge is purely technical, the team says — but entirely within reach. “From what we’ve shown,” they wrote, “it’s now just a tough technical task.”